Ever since the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider debuted, it’s been an essential and wonder-inspiring tool for understanding the building blocks of matter.

December 11, 2025Shannon Brescher Shea

Shannon Brescher Shea (shannon.shea@science.doe.gov) is the social media manager and senior writer/editor in the Office of Science’s Office of Communications and Public Affairs. She writes and curates content for the Office of Science’s Twitter and LinkedIn accounts as well as contributes to the Department of Energy’s overall social media accounts. In addition, she writes and edits feature stories covering the Office of Science’s discovery research and manages the Science Public Outreach Community (SPOC). Previously, she was a communications specialist in the Vehicle Technologies Office in the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. She began at the Energy Department in 2008 as a Presidential Management Fellow. In her free time, she enjoys bicycling, gardening, writing, volunteering, and parenting two awesome kids.

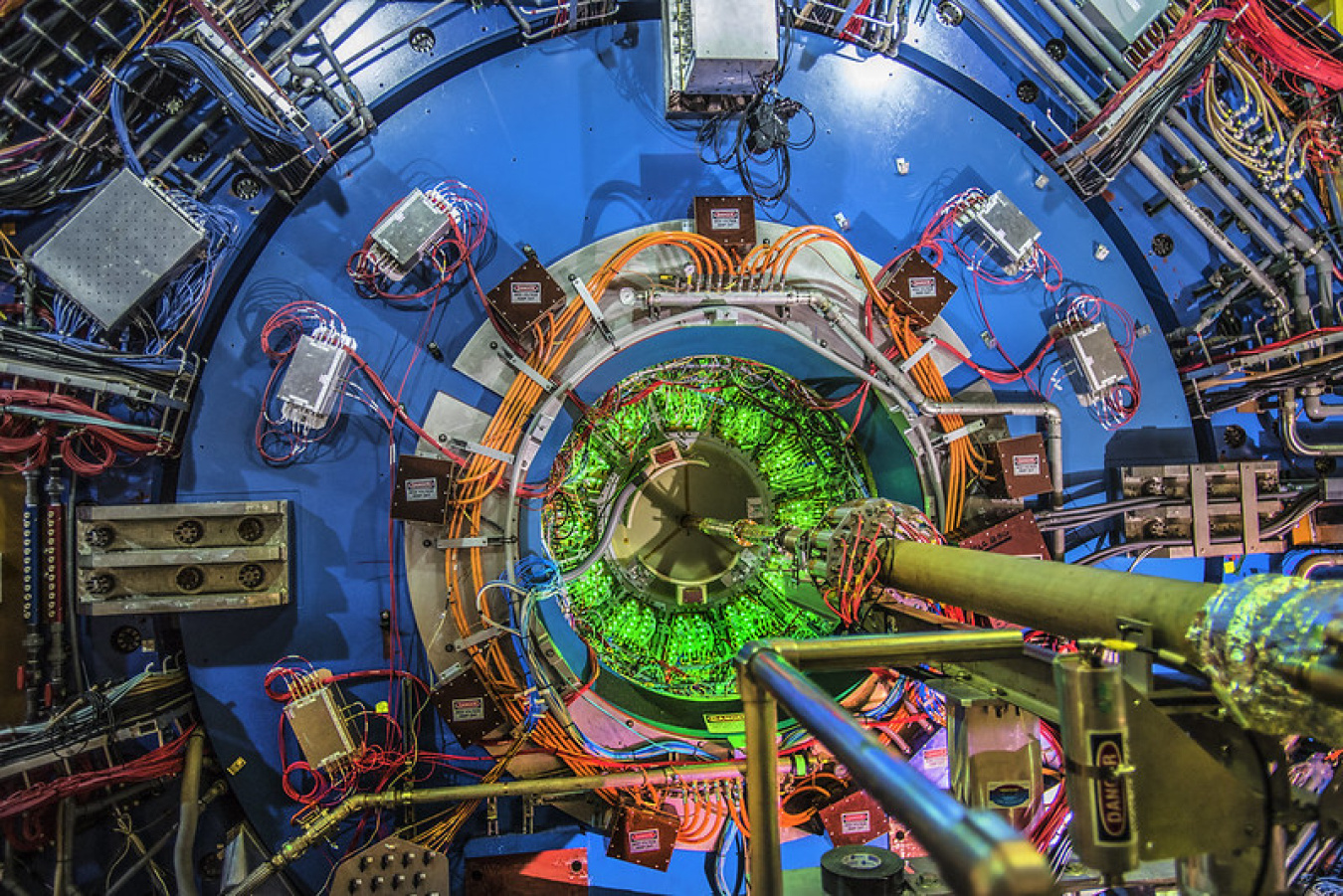

Two huge metal rings, each more than two miles around. Gold ions smashing together at more than 99.99 percent the speed of light. House-size machines with masses of neon green wires.

Inside this set of colossal structures known as the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) roiled a tiny fireball. It was four trillion degrees Celsius, more than 250,000 times hotter than the core of the sun. Here, the building blocks of the universe were emerging. The protons and neutrons that make up ordinary matter were melting into their component particles: quarks and gluons.

This state of matter existed for less than a billionth of a trillionth of a second. But at that moment in 2000, it was the first time in history that humans could study the quark-gluon plasma – although none of the scientists knew they had produced it just yet. Before that, this state of matter had mainly existed previously 13.7 billion years ago, just after the Big Bang.

Crammed together into a control room at 9 PM, scientists watched computer screens burst to life. Previous particle collisions resulted in scattered lines on a screen representing just a few tracks. But this was an eruption of data. The fireworks of 5,000 separate tracks exploded to life in front of them.

At the time, Abhay Deshpande had been working on the project for only a few years. (Now he’s Associate Laboratory Director for Nuclear and Particle Physics at the Department of Energy’s [DOE] Brookhaven National Laboratory [Brookhaven Lab].) Recalling that night, he said, “This is what we live for — to observe and try to explain.”

That moment of astonishment may have been the first time RHIC inspired such a feeling, but it certainly wasn’t the last. Over the last 25 years, the results from RHIC – a DOE Office of Science User Facility – have surprised scientists over and over again. From its initial conception to its final run, RHIC has expanded the world’s understanding of the very building blocks of our universe.

The beginnings of RHIC

RHIC emerged from a tumultuous time in nuclear physics.

While theorists had proposed the idea of quarks in the 1960s, the idea of breaking apart protons and neutrons wasn’t considered until 1974. Surrounded by the beauty of the Hudson Valley, physicists met in New York to discuss delving into the nuclear world. For the first time, they seriously considered the idea of colliding heavy ions. (Ions are atoms that are missing their outer cloud of electrons. Heavy ions have more protons and neutrons than light ions like hydrogen.) This discussion was the genesis of RHIC. A few years later, scientists proposed the idea of the “quark-gluon plasma” that would result from such collisions as well the Big Bang itself.

“We are all products of quark-gluon plasma in the first few microseconds of the universe that cooled,” said Bill Zajc, a professor of physics at Columbia University who has been involved in research at RHIC for decades.

But it wasn’t until 1983 that these ideas came to a head. Brookhaven Lab was in the middle of building a machine to collide protons but other projects were already superseding it before it could be completed. The High Energy Physics Advisory Panel – which provided DOE with guidance on investments – recommended defunding the project. Not long after, the Nuclear Science Advisory Committee (NSAC, which held the same role for nuclear science) recommended a relativistic heavy ion collider as a top priority.

Left with pieces of a partly constructed machine and major aspirations, scientists at Brookhaven Lab decided to think big. They proposed a machine that could produce the quark-gluon plasma. As the NSAC report noted, it would be “a spectacular transition to a new phase of matter.”

Building the technology to create a new state of matter

RHIC smashes together the nuclei of heavy atoms, also called heavy ions. While it only used gold ions for the first two years of operation, it expanded to other types soon after.

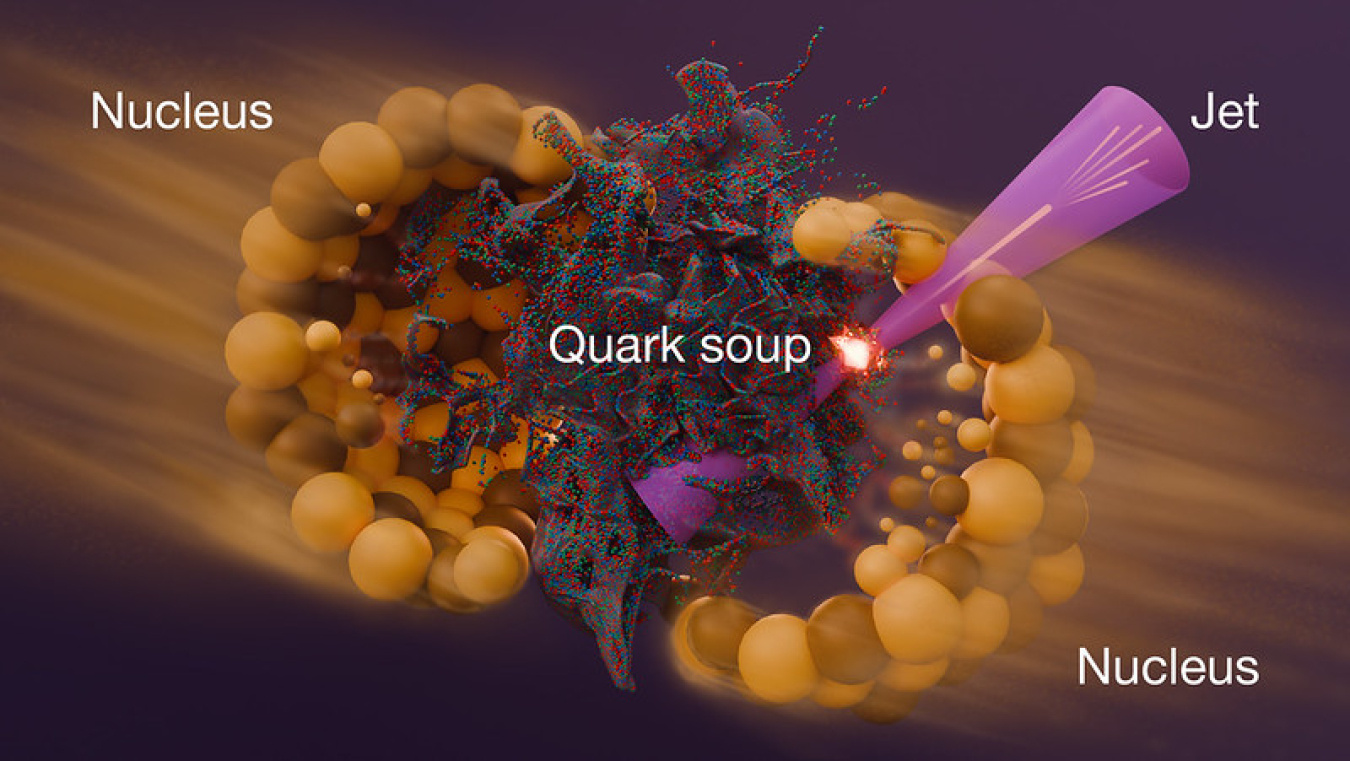

To create and accelerate cylindrical clouds of ions, or beams, RHIC uses two giant rings made up of nearly 2,000 powerful magnets. The beams circulate through the rings in opposite directions and crash into each other at points where the two rings cross. The collisions’ energy is so great that the protons and neutrons in the ions melt into quarks and gluons.

Because it is so difficult to directly collect data from the short-lived “free” quarks and gluons, scientists study the remains of the fireball. As the quark-gluon plasma cools down, the quarks and gluons group up and “freeze” into new particles.

Massive detectors collect data on the identities and movements of these new particles. Scientists then work backwards to investigate the quark-gluon plasma’s characteristics.

RHIC initially had four detectors: STAR, PHENIX, BRAHMS, and PHOBOS. The main piece of STAR was so enormous that it was shipped to the lab on an Air Force plane.

“They were complementary and for good reason,” said Deshpande, referring to STAR and PHENIX. “If you want to find something exciting and if the second detector finds the same thing using complementary techniques and complementary ideas, that's massively important.”

The “ultimate” state of matter

While the scientists hoped RHIC would produce the quark-gluon plasma, knowing what it would look and act like was a different issue.

The standard states of matter are solid, liquid, and gas. As you heat up a material, it moves through those stages. Scientists presumed that the early universe just after the Big Bang was a staggeringly hot gas. Similarly, smashing heavy particles together at close to the speed of light produces extraordinarily high temperatures. These high temperatures reduce the influence of the strong force that holds the quarks and gluons that make up protons and neutrons together. The temperatures melt these nuclear building blocks into their components.

Logically, scientists’ early predictions of the quark-gluon plasma were that it would be a gas. Physicists thought that once protons and neutrons broke apart, the quarks would move freely and not interact.

But the results of the collisions didn’t match those predictions. Instead, the quark-gluon plasma seemed to be acting far more like a liquid than anything resembling a gas.

Controversy and caution

But the RHIC scientists couldn’t just rush out, announcing that they had created the quark-gluon plasma. While the scientists were going to be cautious about the announcement no matter what, an incident not long before that initial collision inspired a particularly careful approach.

Over in Switzerland, physicists at CERN were wrapping up a series of experiments just as RHIC was launching. These experiments used an accelerator that produced collisions at much lower energies than RHIC. Looking to make sense of their results, those scientists put together their thoughts on this more than decade-long program. However, they drew connections from the data that weren’t the most robust.

“Some of the scientists involved in the CERN press release process were there with the best of intentions. From their initial viewpoint, a new era is about to begin at RHIC, [so they] should at least write down [their] impressions of what [they] were able to accomplish,” said Zajc.

Despite the paper not being peer reviewed, CERN put out a press release declaring “New state of matter created at CERN.” It stated that “the experiments … presented compelling evidence” of quarks roaming freely. This description matched the assumption that the quark-gluon plasma would be an ultra-hot gas. Unfortunately, the press release lacked any qualifying statements that might make clear how preliminary these findings were.

The announcement was met with skepticism. Part of the issue was that scientists hadn’t come to a consensus on how to measure the parameters of the collisions to judge whether something was the quark-gluon plasma or not.

“Everybody had their own story. It turned out that most of those did not hang together with other observations,” said Barbara Jacak, a long-time RHIC researcher and physicist with a joint appointment at the University of California, Berkeley and DOE's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. “They all had some aspect of truth, but the conclusions were not very well-supported.”

The announcement sparked a lot of strong feelings on both sides. The responses were so strong that four years after the announcement, the New York Times published an article on the “dueling” scientists that covered a conference where physicists continued to compare results from the two facilities.

“Science is done by people. That means it is subject to passions, it is subject to building consensus, it is subject to personality clashes,” said Jacak.

The skepticism around the CERN announcement only reinforced the RHIC team’s determination to ensure that their data was robust and their papers were peer reviewed.

Running RHIC

The major advantage of RHIC compared to previous facilities – including the ones at CERN – was that it was custom-built for discovering the quark-gluon plasma. Unlike previous experiments, its detectors could measure specific characteristics of the quark-gluon plasma, such as temperature. It could also run baseline and control studies that enabled the scientists to determine if they had truly created the quark-gluon plasma or something else.

By July 2001, all four detectors were recording data from full-energy experiments. Early on, RHIC’s results showed that the scientists were finding something far stranger than their assumptions.

The first was that the particles in the aftermath of the collisions were creating elliptical “flow” patterns. That ellipse shape was a sign that the quarks were strongly interacting in the matter – a very different behavior than the “freely moving” quarks reported by CERN.

The other result was called “jet quenching.” When ions collide, the very high energy of the incoming nuclei is transferred to its quarks and gluons. That energy causes the newly freed quarks and gluons to scatter. Some of them fragment and form sprays of particles called jets. If these jets get caught up in interactions with unbound quarks and gluons as they move through the plasma, they lose energy – the telltale “jet quenching.” By examining the energy of the particles in a jet, scientists can calculate characteristics of the quarks or gluons that created it. Comparing data from jets also suggested a strongly interacting form of matter.

While the scientists had expected some quenching, they didn’t expect it to be so big. “When we first started to see our data, we started to see weird stuff. We saw the jet quenching and we were worried, of course. What could we have messed up?” said Jacak.

The teams poured over the data to make sense of these results.

“The team on the experiment I was leading, PHENIX, was just spectacular. It was really something you wish you could do every day,” said Zajc. “I probably learned more in those two years than I had learned in the previous 20.”

The data sparked intense debate. Every year before their big conference, the 500-person PHENIX team would have a meeting where they would argue passionately about what to say at the conference. At the end, they often piled on a set of buses to the conference together as a bonding experience.

“We could argue like crazy about the meaning of the data and exactly how it was analyzed. But we had these shared scientific goals, and that brought us together and felt like a family,” said Jacak.

Announcing the perfect liquid

By 2005, the four RHIC detector teams felt like they had enough evidence to make a major announcement in a peer-reviewed journal.

“When all of those things became a consistent evolving picture, that's the first time … they made this collective declaration,” said Deshpande. “It was not only to convince ourselves that we were correct but also to convince the rest of the world that we were correct.”

At the April 2005 American Physical Society annual meeting, the panel of presenting scientists gathered at the front of the room and declared that they found “the most perfect liquid ever observed.” It was followed up by a set of papers in the journal Nuclear Physics A.

The state of matter that RHIC was producing had incredibly low viscosity, meaning almost zero resistance to flow. The particles were coordinated in their movement, like water or mercury, only more so. Not only was this state of matter not a gas, it was the epitome of a friction-free fluid.

While many of the RHIC scientists thought they had produced the quark-gluon plasma, they decided to focus on the properties they had measured instead of a name. This conception of the quark-gluon plasma was so radically different from what the community expected that the team wanted people to focus on its characteristics more than its label.

“I think it’s fair to say that most of us had just simply not envisioned quark-gluon plasma having that property as the defining property,” said Zajc. “For many of us, it was a revelation.”

The quark-gluon plasma revealed!

All along, the RHIC scientists were continuing to gather evidence that they had, in fact, produced the quark-gluon plasma. In February 2010, they felt confident announcing it.

“We wanted to be sure that there were enough observations that you couldn’t come up with some other way to explain them away,” said Jacak. “It was a crazy exciting time.”

Presenting at the APS conference, the collaborations came together to present the results. At the symposium, the teams announced that they had measured the temperature of the perfect liquid to a high enough accuracy to declare it was the quark-gluon plasma – four trillion degrees Celsius. This was far higher than the temperature needed to melt protons and neutrons. The groups presented other types of supporting evidence as well.

Exploring the quark-gluon plasma

With both the perfect liquid characteristic and the quark-gluon plasma being identified, physicists were eager to jump into better understanding this state of matter.

The perfect liquid characteristic made the discovery of quark gluon plasma far more interesting than if it had matched scientists’ assumptions. Over time, the RHIC teams realized it had similar properties to other forms of matter under extreme conditions. At a plasma conference, Jacak had a revelation. Listening to scientists from the National Ignition Facility at DOE’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, she realized how much their work had in common. She said, “For me, it was just mind blowing. We actually know how this works.”

This meant that the results from RHIC weren’t just revolutionary to nuclear physics but to other areas of science as well.

Collaborating with CERN

Setting aside their disagreements, the teams at CERN and RHIC dove into the data. By 2012, new experiments at CERN that smashed together lead ions produced the quark-gluon plasma. Scientists there found it had the same perfect liquid characteristic as the matter at RHIC, although the temperature was about 50 percent hotter. The collaborations developed a mathematical model to describe the characteristics of quark-gluon plasma as a perfect fluid.

The two sets of experiments went back and forth, taking advantage of each other’s strengths. While the Large Hadron Collider at CERN could produce higher energy collisions and measure a wider variety of particles, RHIC could access the lower end of the energy spectrum and uniquely explore the transition from ordinary matter to the quark-gluon plasma. The RHIC team would observe features in their data and then the team at Large Hadron Collider would investigate those features more deeply. That data would inform RHIC’s next data collection.

“There’s plenty of physics to go around. The CERN/LHC heavy ion program is doing things that RHIC simply couldn’t do,” said Zajc.

Surprises from heavy quarks and light ions

As they studied it, the quark-gluon plasma just kept confounding scientists’ expectations.

While the flow of the quark-gluon plasma was unquestionably powerful, scientists underestimated exactly how powerful it was. Common sense indicated that there was no way that uncommon “heavy” quarks could get caught up in the plasma’s swirl. It would be like dropping a boulder in a river and watching it flow downstream instead of sinking.

But evidence started to pile up otherwise. Instead of the heavy quarks plowing through, the scientists observed them losing a lot of energy. The “river” of the quark-gluon plasma was far more effective at pulling along the boulder-like heavy quarks than expected. Finding this phenomenon came in handy – these heavy quarks also helped scientists more precisely measure the plasma’s temperature.

Similarly, scientists first thought that collisions between light ions simply wouldn’t have enough protons and neutrons to create the quark-gluon plasma. But once again, RHIC would prove those assumptions wrong.

As early as 2003, scientists collided very light deuterium ions with gold ions. The researchers ran these collisions to provide a baseline to compare to the gold-gold collisions. Seeing certain patterns in the collisions between gold ions would indicate they had created the quark-gluon plasma.

When the researchers looked at the collisions with the highest number of produced particles, they saw the patterns in the gold collisions. But to their surprise, they saw the elliptic flow in the light ion collisions as well.

“This was a happy win for the scientists because we found something completely different than we anticipated,” said Deshpande. “I think that that was a very beautiful thing that happened.”

Later studies revealed this behavior indicating the quark-gluon plasma from smaller and smaller collisions. Scientists even saw signs of it in collisions between photons (particles of light) and heavy ions.

“We do have this embarrassment of riches and ubiquity of what appears to be quark-gluon plasma in even the smallest collisions,” said Zajc. “The question is, what’s the smallest blob we can make that exhibits the quark-gluon plasma properties?”

Mapping the phase diagram

While the quark-gluon plasma keeps showing up in unexpected ways, scientists are still searching to find the line between ordinary matter and quark-gluon plasma.

Just as water can be solid, liquid, or gas at certain temperatures, RHIC scientists want to develop a similar phase graph that shows where ordinary nuclear matter turns into the quark-gluon plasma. What conditions of temperature and density could create that clear transition?

The scientists are particularly interested in identifying what’s called the critical point. This is a point at which there ceases to be an abrupt transition between states of matter. Identifying this critical point would not only give them insight into quark-gluon plasma but also matter in neutron stars.

“If we find the phase transition, the critical point, we will find something new,” said Deshpande. “If we don’t find it, that will also create something new. It’s no-lose situation.”

To figure out “where to look,” the RHIC team ran a beam energy scan. For this process, they created collisions at energies running from very low to very high. At each level, researchers looked for big fluctuations in the balance between types of particles – a key characteristic of a phase transition. In this way, they could eliminate different combinations of temperature and pressure to find the critical point. The scientists found suggestions of a possible boundary; collisions with energy around 19.6 billion electron volts (GeV) seemed to be a particularly important spot. However, the scientists haven’t yet found a definitive boundary line or critical point.

“The STAR experiment has done a heroic effort to try to locate it,” said Zajc.

The next generation of nuclear physics

With RHIC having met its major science goals, it’s marking its final run in 2025. This year alone, researchers are expecting to gather data on more than 60 billion particle collision events. They expect it to take at least six to eight years to process all of that data.

Other researchers are helping design and construct a complete transformation of RHIC into an Electron-Ion Collider (EIC). The DOE Office of Science’s next nuclear physics User Facility will reuse parts of RHIC and add new equipment. In contrast to RHIC’s heavy ions, the Electron-Ion Collider will collide protons or ions with tiny electrons. These collisions will be downright cold compared to the quark-gluon plasma’s blazing hot matter. Unlike RHIC’s focus on understanding the beginning of the universe, this cold nuclear matter makes up the matter we see and interact with every day. The research at the EIC will also build upon the other major research focus of RHIC besides the quark-gluon plasma – understanding proton spin. By revealing the internal structure of protons and ordinary nuclei, the Electron-Ion Collider will give insights into how quarks and gluons are held together by the strongest force in nature.

“I want to be around when the first collisions start happening at the EIC,” said Jacak. “I think those collisions – which will probe the structure of the cold, dense gluons deep in the heart of nuclei – will be amazing.”

From the quark-gluon plasma to the strangeness of ordinary nuclear matter, nuclear physics is helping us understand our past and present. Tools like RHIC and the Electron-Ion Collider help us look ever deeper into the matter that surrounds us.

“When you find something in the lab that matches theory, that’s not the experimentalists’ dream day,” said Deshpande. “It is when you find something that’s completely different than theory tells you, that’s when you learn something new.”