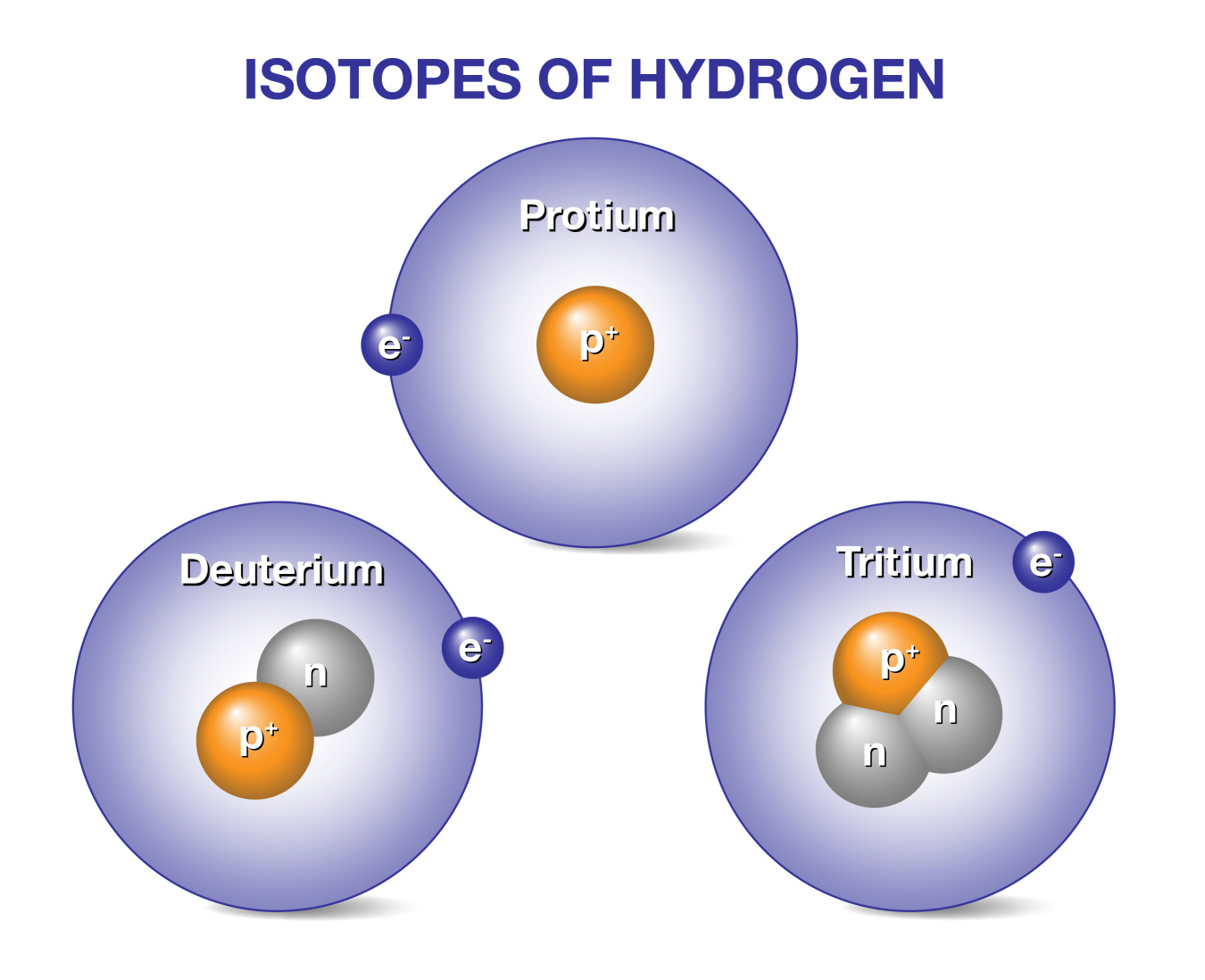

Deuterium and tritium are promising fuels for producing energy in future power plants based on fusion energy. Fusion energy powers the Sun and other stars through fusion. Deuterium and tritium are isotopes of hydrogen, the most abundant element in the universe. While all isotopes of hydrogen have one proton, deuterium also has one neutron and tritium has two, so their ion masses are heavier than protium, the isotope of hydrogen with no neutrons. When deuterium and tritium fuse, they create a helium atom, which has two protons and two neutrons, and an energetic neutron. These energetic neutrons could be the basis for generating energy in future fusion power plants.

On Earth, fusion has the potential to supply safe, clean, and relatively limitless energy. However, there are requirements to make these power plants a reality. One key requirement is identifying a viable fuel to sustain fusion. Fusion can occur with elements weighing less than iron. But most elements will not fuse unless they are in the interior of a star. To create burning plasmas in experimental fusion power plants such as tokamaks and stellarators, scientists seek a fuel that is available and relatively easy to produce and store. One current possibility is deuterium-tritium fuel. This fuel reaches fusion conditions at lower temperatures than other elements and releases more energy than other fusion reactions. Future commercially feasible fusion plants would need a robust supply chain for both hydrogen isotopes.

Deuterium is common: about 1 out of every 6,500 hydrogen atoms in seawater is in the form of deuterium. This means our oceans contain many tons of this hydrogen isotope. The fusion energy released from just 1 gram of deuterium-tritium fuel equals the energy from about 2,400 gallons of oil.

Tritium is not common. It is a radioactive isotope that decays relatively quickly, with a 12-year half-life. It is rare in nature and not immediately available for use in potential power plants. However, there is a process to produce tritium. For example, exposing the more common element lithium to energetic neutrons can generate tritium through low-energy nuclear fission. Scientists are actively researching how to produce tritium, a process called breeding, as part of a subsystem of a fusion power plant at the rate needed to make future power plants self-sufficient for their tritium supply. Tritium breeding systems will require enriched lithium, specifically the isotope lithium-6 (with three protons and three neutrons). Since lithium-6 is far less abundant than other lithium isotopes, scientists are actively researching lithium isotope separation with an emphasis on scalable, environmentally friendly methods.

DOE Office of Science: Contributions to Deuterium-Tritium Fuel

Part of the mission of the Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science, Fusion Energy Sciences (FES) program is to develop a practical fusion energy source. FES works with the Advanced Scientific Computing Research program using scientific computing to advance fusion science and understand the effect of ion mass on various plasma phenomena. At Office of Science user facilities such as the DIII-D tokamak and NSTX-U spherical tokamak, scientists study the impact of ion mass on plasma confinement, transport, and turbulence. The confinement of fusion products such as the helium ion is also studied in the presence of helical magnetic fields. The Office of Science Nuclear Physics program develops the fundamental nuclear science underpinning the understanding of fusion by creating nuclear reaction databases, generating nuclear isotopes, and studying aspects of nucleosynthesis.

DOE is also working to establish robust supply chains for lithium for fusion energy. One of DOE’s missions is to steward the fundamental science underlying the curation of nuclear materials, establish the applied engineering capabilities that can supply the needed materials, and create the commercial opportunities for private companies to establish and expand the necessary supply chains. As the fundamental science underlying fusion becomes more firmly established, the focus of DOE programs is shifting to address fusion fuel supply chains and other fusion challenges that scientists and engineers must solve before our homes and industries are powered by fusion.

Deuterium-Tritium Fuel Facts

- Water made from deuterium is about 10 percent heavier than ordinary water. That’s why it is sometimes referred to as “heavy water.” It would sink to the bottom of a glass of ordinary water.

- Tritium exists on Earth because of natural production from interactions with cosmic rays (albeit in quantities insufficient for energy production), some types of energy-producing nuclear fission reactors such as the heavy-water CANDU reactor, and nuclear weapons testing.

- Lithium is an element created in the primordial universe. In 2023, the U.S. Geological Survey reports that the identified world resources total as much as 98 million tons (up from 89 million tons in 2022) and reserves total 26 million tons (up from 22 million tons in 2022). Continued exploration identifies new resources each year. The natural relative abundance of lithium-6 is 7.5% of lithium overall, with lithium-7 making up the balance.

- To avoid certain research and development challenges including structural material damage from energetic neutrons, fusion scientists are interested also in aneutronic fusion reactions (such as deuterium-helium-3 and proton-boron fusion) even though these fusion reactions occur at higher ion temperatures than for deuterium and tritium. Similar to deuterium-tritium-based fusion, power plant designs using these reactions will face supply chain challenges that must be overcome before fusion energy can contribute significantly to the world’s energy needs.

Resources and Related Terms

- DOE Office of Science Fusion Energy Sciences program

- Science Up-Close: Developing a Cookbook for Efficient Fusion Energy

- Fusion Research Ignites Innovation

- Learn about joint DOE-private sector efforts to advance fusion power in these presentations from a June 2022 workshop.

Scientific terms can be confusing. DOE Explains offers straightforward explanations of key words and concepts in fundamental science. It also describes how these concepts apply to the work that the Department of Energy’s Office of Science conducts as it helps the United States excel in research across the scientific spectrum.