Distinguished Scientist Fellow Mary Bishai shares her reflections on a career investigating the mysterious particles called neutrinos.

February 4, 2026Shannon Brescher Shea

Shannon Brescher Shea (shannon.shea@science.doe.gov) is the social media manager and senior writer/editor in the Office of Science’s Office of Communications and Public Affairs. She writes and curates content for the Office of Science’s Twitter and LinkedIn accounts as well as contributes to the Department of Energy’s overall social media accounts. In addition, she writes and edits feature stories covering the Office of Science’s discovery research and manages the Science Public Outreach Community (SPOC). Previously, she was a communications specialist in the Vehicle Technologies Office in the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. She began at the Energy Department in 2008 as a Presidential Management Fellow. In her free time, she enjoys bicycling, gardening, writing, volunteering, and parenting two awesome kids.

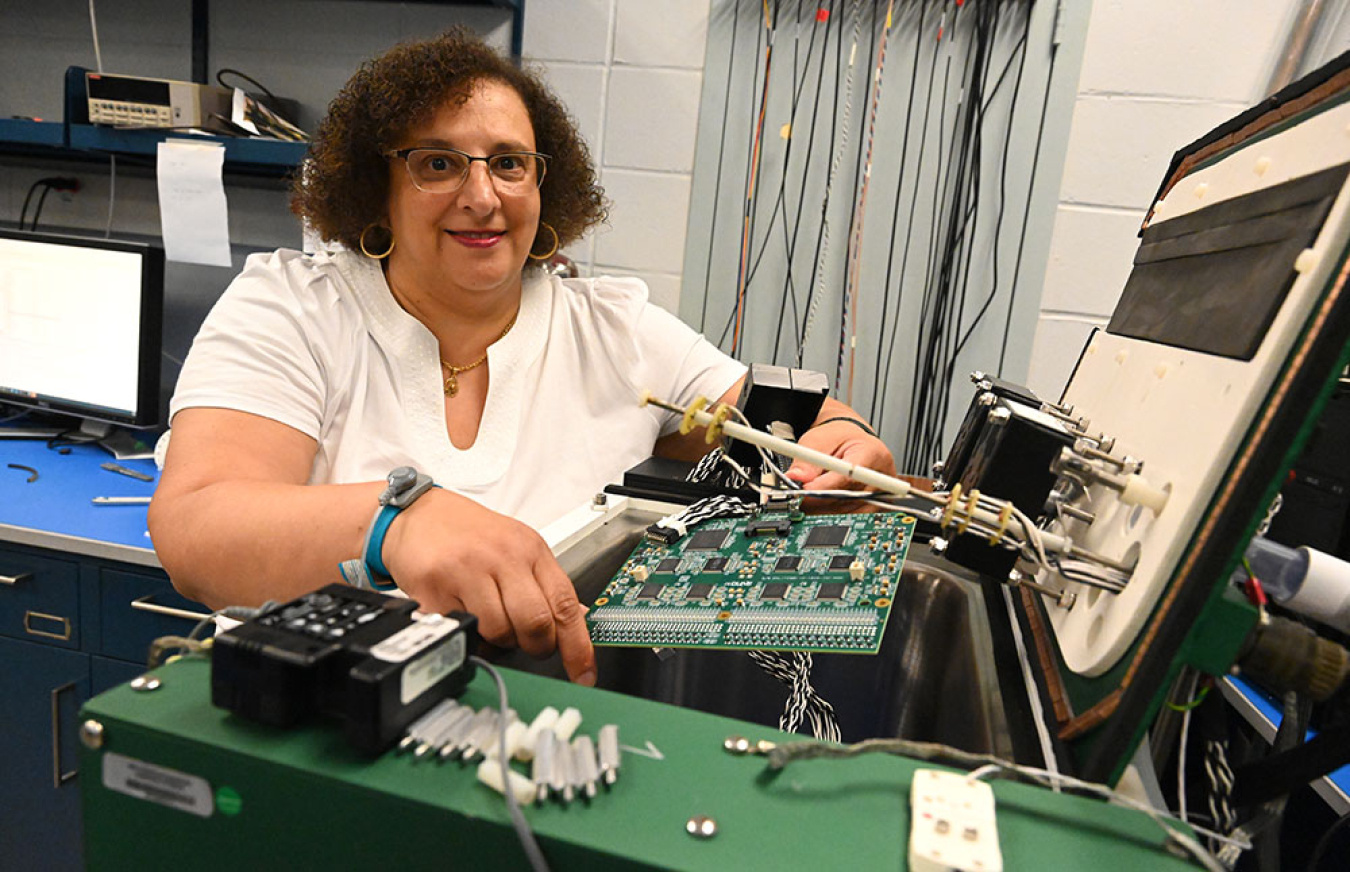

Scientists recognized by the Department of Energy Office of Science Distinguished Scientists Fellows Award are pursuing answers to science’s biggest questions. Mary Bishai is a senior physicist at DOE’s Brookhaven National Laboratory.

If it wasn’t for a magazine, I may have become a completely different type of scientist.

In 1985, my uncle – who was a prominent marine biology professor – was tutoring me in high school biology. As a science lover, he had copies of National Geographic lying around. Intrigued, I convinced my parents to get me a subscription. One article caught my eye – “Worlds Within the Atom.” It described how physicists used massive particle accelerators to study the tiniest things in existence.

Even though I was born in and living in Egypt, I was enthralled by the research in Europe and the United States. I decided I would one day work at CERN in Switzerland or the Tevatron collider at the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Fermilab.

Although my engineer parents wanted me to follow in their footsteps, I entered the American University of Cairo as a physics major instead. An exchange program later brought me to the United States.

Then nearly 13 years after I first read about the Tevatron at Fermilab, I was there. Fulfilling my dream, I delved into the interactions between the fundamental particles called quarks.

But that’s not the end of the story. Along the way, another type of physics caught my eye – neutrino physics. Since then, I’ve pursued the question - how can neutrinos help us answer some of the biggest questions about how our universe evolved?

The little neutral one

Neutrinos are a type of fundamental particle. They’re in a group called the leptons, which also includes electrons. However, neutrinos are much smaller than their familiar cousins.

Neutrinos are incredibly abundant. On the tip of your tongue right now, there are 300 neutrinos left over from the Big Bang. The sun, supernovae, cosmic rays interacting with the atmosphere, and nuclear reactors also produce neutrinos. They’re the second most abundant particle in the universe, after photons (particles of light). Neutrinos are everywhere.

Despite them being so common, neutrinos interact very little with other matter. Every second, 100 billion neutrinos produced by the sun move through your thumbnail and never leave a mark. A neutrino would have to travel 1.6 light years through lead – or 100,000 times the distance from the Earth to the sun – to interact with a single atom. Or as writer John Updike declared in the poem “Cosmic Gall,” “The earth is just a silly ball / To them, through which they simply pass, / Like dustmaids through a drafty hall / Or photons through a sheet of glass.” This lack of interaction inspired the nickname of “ghost particles.”

Scientists are interested in neutrinos because of their ubiquity and the fact that they could hold the answers to some of physics’ biggest questions. One of those questions is the issue of why there is something in our universe rather than nothing.

But none of that drew me to neutrino research. Wave-particle duality – or the idea that all matter can act like waves or particles – is a key concept in quantum mechanics. Scientists in the 1960’s stipulated that if neutrinos have non-zero mass, one type of neutrino could convert to another then back again. This would be a direct signature of quantum interference and wave-particle duality. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, experimental results confirmed the observation of neutrino “oscillations.” Hearing about one of the experiments, I said, “Oh my God, this is wave particle duality. It’s quantum mechanics and it’s just there. That’s cool, that’s what I want to do.”

When I joined DOE’s Brookhaven National Laboratory in 2004 to study neutrinos, I joined a history of “ghostbuster” physicists.

A history of ghostbusters

Our story starts in the 1930s. At that point, scientists were interested in how radioactive particles fall apart. Beta decay is when a nucleus emits an electron or its anti-matter partner, the positron. When a nucleus undergoes beta decay, it transforms into another type of nucleus. When scientists looked at this process, they expected it to release a specific amount of energy. But it didn’t. It seemed like this result contradicted the Law of Energy Conservation, where energy can neither be created nor destroyed.

Enter our first ghostbuster – Wolfgang Pauli. In a letter to fellow physicists attending a workshop, he proposed the idea of a yet-unknown particle that would carry away some of the energy. It would be neutral and have extremely small mass. While he valued his research enough to write the letter, it didn’t win out over a social obligation. In the same letter, he explained that he couldn’t have traveled to the workshop “since I am indispensable here in Zurich because of a ball.” Physicists do like to party.

Now let’s jump ahead to the 1950s at DOE’s Los Alamos National Laboratory. Determined to track down these mysterious particles, Fred Reines and Clyde Cowan pursued the “poltergeist project.” While they first proposed detecting neutrinos from nuclear bomb testing, that idea was dismissed. Instead, they placed particle detectors near the Hanford and Savannah River nuclear reactors. The detectors sensed a telltale: two flashes of light from ghost-like neutrinos emitted by the reactors interacting with the material in the detectors. By counting these flashes, the scientists could count the neutrinos being captured by the detector. Developing the first neutrino detector netted Reines the Nobel Prize in 1995.

In addition to reactors, scientists realized that they could produce neutrinos in particle accelerators. From early on, Brookhaven was a leader in neutrino research. Physicists Leon Lederman, Melvin Schwartz, and Jack Steinberger used a proton beam from Brookhaven’s Alternating Gradient Synchrotron to slam protons into a target. A type of particle called a pi meson emerged, which then decayed into a neutrino and a muon (another cousin of the electron).

The scientists wanted to know if these were the same type of neutrinos as the ones from beta decay. The tracks the neutrinos left in their detector revealed mostly muon neutrinos and not electron neutrinos which are the type of neutrinos from beta decay. Another Nobel Prize-winning discovery. Later experiments at Fermilab confirmed a third type of neutrino called the tau neutrino - the neutral partner of the tau lepton, the heavier sibling of electrons and muons.

But both reactors and accelerators are made by humans. What about neutrinos from the sun? That was Ray Davis’s question. A chemist and physicist from Brookhaven, Davis began a long-standing physics experiment in 1967. He wanted to test the models that predicted how many solar neutrinos Earth receives.

Davis installed a particle detector with 615 tons of cleaning fluid in the Homestead gold mine in South Dakota. The solar neutrinos interacted with the chlorine in the cleaning fluid to produce a unique isotope – argon-37. To track the interactions, he painstakingly counted the atoms of argon-37. He kept this up for almost 20 years! For demonstrating how to detect solar neutrinos, he also received a Nobel Prize.

As these experiments revealed different types of neutrinos – called “flavors” – they also brought up new questions. From studying beta decay, scientists knew that neutrinos are extraordinarily light. In fact, they assumed that neutrinos didn’t have mass at all, like photons. But observations suggested that assumption was wrong.

In the late 1950s to 1960s, scientists suggested that the different flavors of neutrinos were different mixes of quantum states. In highly relativistic particles like neutrinos, mass, energy, and momentum are all closely related. So when neutrinos act like waves and not particles, you can use their speed to understand their mass. If the different flavors had different speeds, neutrinos would have to have mass. One sign of neutrinos having mass would be one flavor of neutrino turning into another.

While theory supported that idea, no one had observed that behavior – at least not until 1998 at the Super-Kamiokande (Super-K) detector. This experiment studied neutrinos created by cosmic rays smacking into the atmosphere. It identified if they were muon or electron neutrinos, as well as the direction they came from. The number of neutrinos that came from near the experiment matched well with estimates. In contrast, the ones from far away had a major deficit. The “disappearing” neutrinos were the first observations of neutrinos changing flavor, called oscillation.

Later experiments confirmed the idea of neutrino oscillation. They also gave evidence of at least three different masses. The results won the leaders of the Super-K and Sudbury Neutrino Observatory experiments yet another Nobel Prize.

From not knowing that neutrinos existed to realizing that they change flavors over time, a lot changed in neutrino science in 60 years. But there was so much we still didn’t know.

Becoming a ghostbuster

This is where I come back into the story. The results from the KamLAND experiment following the Super-K project were so intriguing that I wanted to study this bizarre particle.

One of the earliest projects I worked on was the Daya Bay experiment. This was an extremely difficult project. This experiment measured neutrinos from one of the most powerful nuclear reactors in the world. We had three detectors: one close to the reactor core, one a few hundred meters away, and a last one about a kilometer away. Spreading out the detectors allowed us to study the differences between them. Taking data over the course of 10 years, we detected 5 million anti-neutrino interactions! They were the most precise measurements in the world of antineutrinos from reactors.

With these results, we knew there were three mass states and three flavors of neutrino. Each mass state is a different mix of flavors. The first mass state is dominated by the electron neutrino flavor. The second mass state has almost equal amounts of all three types. The third mass state is almost all muon and tao neutrino with a tiny amount of electron neutrinos. While we knew the second mass state was heavier than the first one, we didn’t know if the first mass state was heavier or lighter than the third one.

These flavors and mass states brought up a new question – could neutrinos explain why there is something rather than nothing? There is a fundamental principle called charge-parity symmetry. It states that if a particle is swapped with its anti-particle and left and right are swapped, the laws of physics will act in an identical way. However, if this law was universally true, there would have been equal amounts of matter and anti-matter at the beginning of the universe. As matter and anti-matter completely destroy each other and the universe is dominated by matter, we know there must be an exception. If neutrinos and anti-neutrinos demonstrate different mixing of neutrino flavors, this could be the exception. But to find out, we needed to better understand how neutrinos change flavor.

The ultimate neutrino experiment

Exploring this issue was why we designed the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE).

In the early 2000s, a multidisciplinary, multi-institutional team proposed the ultimate neutrino experiment. We picked two facilities with a long history of neutrino research – the former Homestake Mine and Fermilab. Where Ray Davis once studied solar neutrinos is now home to the Sanford Underground Research Facility. Fermilab has a particle accelerator that produces the most powerful neutrino beam in the world. The locations are 1,300 kilometers apart, enough space for us to capture plenty of oscillations.

Besides the sheer distance, DUNE is extremely large and complex. From the beam line to the shielding, everything must be extremely precise. The detectors use 17 kilotons of liquid argon that must be kept at -300 degrees F. Each of the two cryostats that keep the liquid cold is the size of a Boeing 787 plane. To fit the equipment, we had to massively expand the underground space of the former mine.

In addition to detecting neutrino oscillation, DUNE should also provide us with new insights into other issues. It will look for new particles, several types of proton decay, and neutrinos produced by supernovas.

Recognizing the importance of this experiment, more partners joined the effort. Currently, we have 1,400 scientists from 209 institutions. Our international partners at CERN and elsewhere have made essential contributions to building and testing parts of the detectors.

I have been involved with DUNE since early in its conception and served as DUNE project scientist from 2012 to 2015, leading the conceptual design of the project. I was also honored to serve as DUNE co-spokesperson from 2023 to 2025. In August 2024, we celebrated our biggest milestone yet – the ribbon cutting of the cavern expansion. The next milestone will be installing the first of four detectors underground.

Looking forward, I hope that DUNE provides the next generation of scientists and engineers with the same opportunities I had. Working in experimental particle physics at the DOE National Labs has given me the incredible opportunity to study the fundamental science of our universe. I am lucky to study the worlds within the atom that I first read about in a magazine 40 years ago.