Biomass can be converted directly into liquid fuels, called "biofuels," to help meet transportation fuel needs. The two most common types of biofuels in use today are ethanol and biodiesel, both of which represent the first generation of biofuel technology.

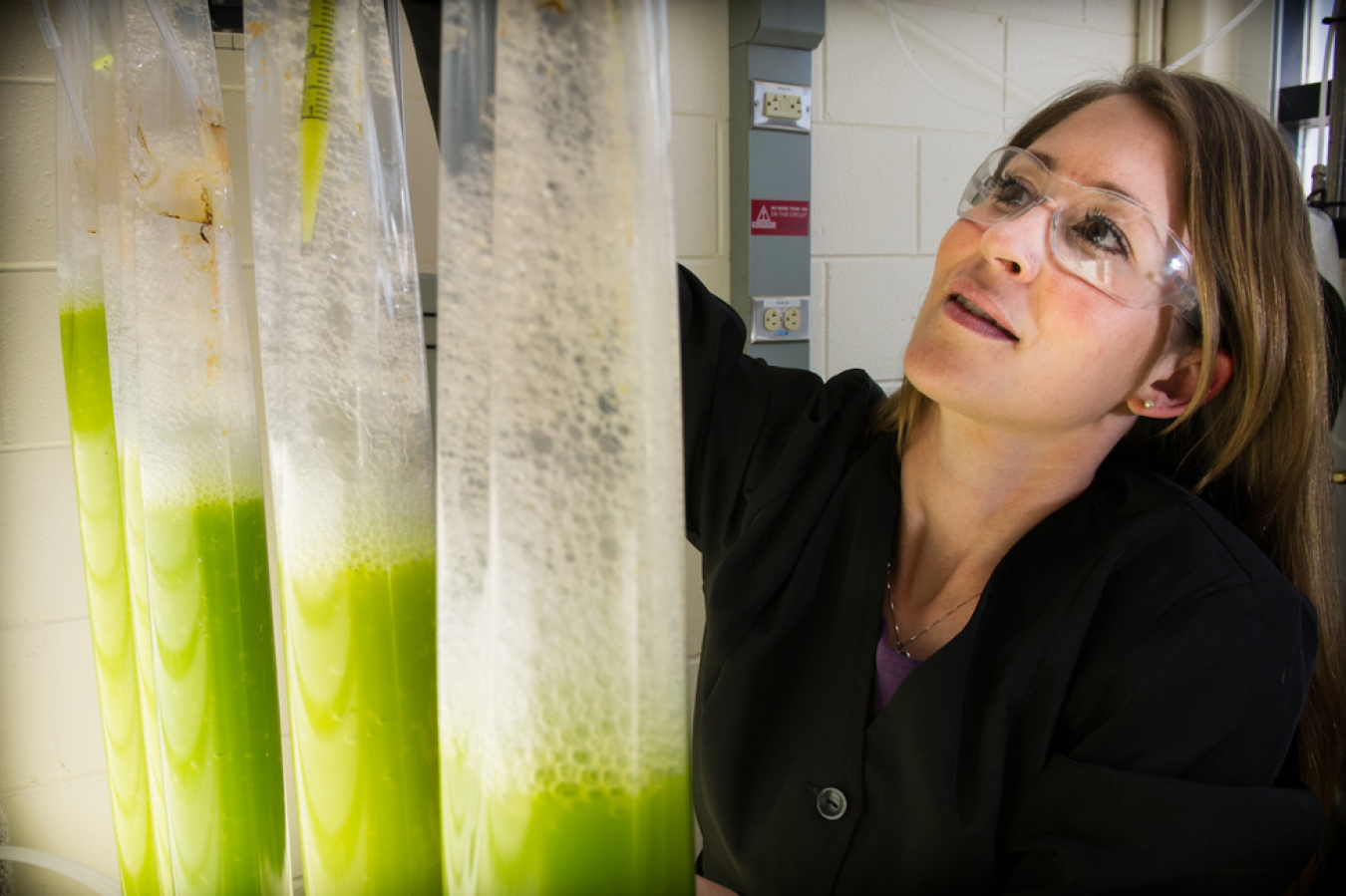

NLR Post Doc Brenna Black draws samples from a tubular bag photobioreactor, to inoculate new growth media, at the Algal Research Lab at the National Laboratory of the Rockies (NLR) in Golden, CO. Photo by Dennis Schroeder, NLR

The Bioenergy Technologies Office (BETO) is collaborating with industry to develop next-generation biofuels made from wastes, cellulosic biomass, and algae-based resources. BETO is focused on the production of hydrocarbon biofuels—also known as “drop-in” fuels—which can serve as additional petroleum resources in existing refineries, tanks, pipelines, pumps, vehicles, and smaller engines.

ETHANOL

Ethanol (CH3CH2OH) is a type of fuel that can be made from various plant materials, collectively known as “biomass.” Ethanol is an alcohol used as a blending agent with gasoline to increase octane.

The most common blend of ethanol is E10 (10% ethanol, 90% gasoline) and is approved for use in most conventional gasoline-powered vehicles up to E15 (15% ethanol, 85% gasoline). Some vehicles, called flexible fuel vehicles, are designed to run on E85 (a gasoline-ethanol blend containing 51%–83% ethanol, depending on geography and season), a fuel with much higher ethanol content than regular gasoline. Roughly 97% of gasoline in the United States contains some ethanol.

Most ethanol is made from plant starches and sugars—particularly corn starch in the United States—but scientists are continuing to develop technologies that would allow for the use of cellulose and hemicellulose, the non-edible fibrous material that constitutes the bulk of plant matter.

The common method for converting biomass into ethanol is called fermentation. During fermentation, microorganisms (e.g., bacteria and yeast) metabolize plant sugars and produce ethanol.

Learn more about Ethanol.

BIODIESEL

Biodiesel is a type of biodegradable liquid biofuel, such as new and used vegetable oils and animal fats and can be a supplement to petroleum-based diesel fuel. Biodiesel is nontoxic and is produced by combining alcohol with vegetable oil, animal fat, or recycled cooking grease.

Like petroleum-derived diesel, biodiesel is used to fuel compression-ignition (diesel) engines. Biodiesel can be blended with petroleum diesel in any percentage, including B100 (pure biodiesel) and, the most common blend, B20 (a blend containing 20% biodiesel and 80% petroleum diesel).

Learn more about Biodiesel.

BIOMASS-BASED HYDROCARBON "DROP-IN" FUELS

Petroleum fuels, such as gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel, contain a complex mixture of hydrocarbons (molecules of hydrogen and carbon), which are burned to produce energy. Hydrocarbons can also be produced from biomass sources through a variety of biological and thermochemical processes. Biomass-based hydrocarbon fuels are nearly identical to petroleum-based fuels—so they're compatible with today's engines, pumps, and other infrastructure.

Learn more about Hydrocarbon Fuels.

BIOFUEL CONVERSION PROCESSES

Deconstruction

Producing advanced biofuels (e.g., cellulosic ethanol and bio-based hydrocarbon fuels) typically involves a multistep process. First, the tough rigid structure of the plant cell wall—which includes the biological molecules cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin bound tightly together—must be broken down. This can be accomplished in one of two ways: high temperature deconstruction or low temperature deconstruction.

High-Temperature Deconstruction

High-temperature deconstruction makes use of extreme heat and pressure to break down solid biomass into liquid or gaseous intermediates. There are three primary routes used in this pathway:

- Pyrolysis

- Gasification

- Hydrothermal liquefaction.

During pyrolysis, biomass is heated rapidly at high temperatures (500°C–700°C) in an oxygen-free environment. The heat breaks down biomass into pyrolysis vapor, gas, and char. Once the char is removed, the vapors are cooled and condensed into a liquid “bio-crude” oil.

Gasification follows a slightly similar process; however, biomass is exposed to a higher temperature range (>700°C) with some oxygen present to produce synthesis gas (or syngas)—a mixture that consists mostly of carbon monoxide and hydrogen.

When working with wet feedstocks like algae, hydrothermal liquefaction is the preferred thermal process. This process uses water under moderate temperatures (200°C–350°C) and elevated pressures to convert biomass into liquid bio-crude oil.

Low-Temperature Deconstruction

Low-temperature deconstruction typically makes use of biological catalysts called enzymes or chemicals to breakdown feedstocks into intermediates. First, biomass undergoes a pretreatment step that opens up the physical structure of plant and algae cell walls, making sugar polymers like cellulose and hemicellulose more accessible. These polymers are then broken down enzymatically or chemically into simple sugar building blocks during a process known as hydrolysis.

Upgrading

Following deconstruction, intermediates such as crude bio-oils, syngas, sugars, and other chemical building blocks must be upgraded to produce a finished product. This step can involve either biological or chemical processing.

Microorganisms, such as bacteria, yeast, and cyanobacteria, can ferment sugar or gaseous intermediates into fuel blendstocks and chemicals. Alternatively, sugars and other intermediate streams, such as bio-oil and syngas, may be processed using a catalyst to remove any unwanted or reactive compounds in order to improve storage and handling properties.

The finished products from upgrading may be fuels or bioproducts ready to sell into the commercial market or stabilized intermediates suitable for finishing in a petroleum refinery or chemical manufacturing plant.

Read more about BETO's Conversion Technologies program.