On the Army's 250th Birthday, we remember how its oversight of the Manhattan Project laid the foundation for the NNSA

National Nuclear Security Administration

June 13, 2025When people think of America’s nuclear deterrent and the modern Nuclear Security Enterprise, they might not immediately associate it with the U.S. Army. However, as the Army celebrates its 250th birthday on June 14, we at NNSA remember the crucial role that the U.S. Army played in the formation and administration of the Manhattan Project – the foundation of today’s Nuclear Enterprise and the beginning of a new atomic age thanks to the collaboration between soldiers, scientists, industrialists, and engineers during World War II.

While the Army and Navy were involved in the study of uranium prior to the start of World War II, the atomic project’s militarization did not begin in earnest until June 1942, when growing security concerns suggested placing the program within one of the armed forces. The Army Corps of Engineers’ construction expertise made it the logical choice to build the production facilities envisioned. President Franklin Roosevelt approved turning over three critical tasks to the Army:

- the design, construction, and operation of plants to produce fissionable materials;

- the organization of a special laboratory to design, manufacture, and test atomic weapons;

- and the responsibility for security for the entire project.

The Corps of Engineers thus created a new engineer district in New York City to administer the project, appropriately naming it the Manhattan Engineer District. As the Department of Energy’s official history of the Manhattan Project notes, “With this reorganization in place, the nature of the American atomic bomb effort changed from one dominated by research scientists to one in which scientists played a supporting role in the construction enterprise run by the United States Army Corps of Engineers.”

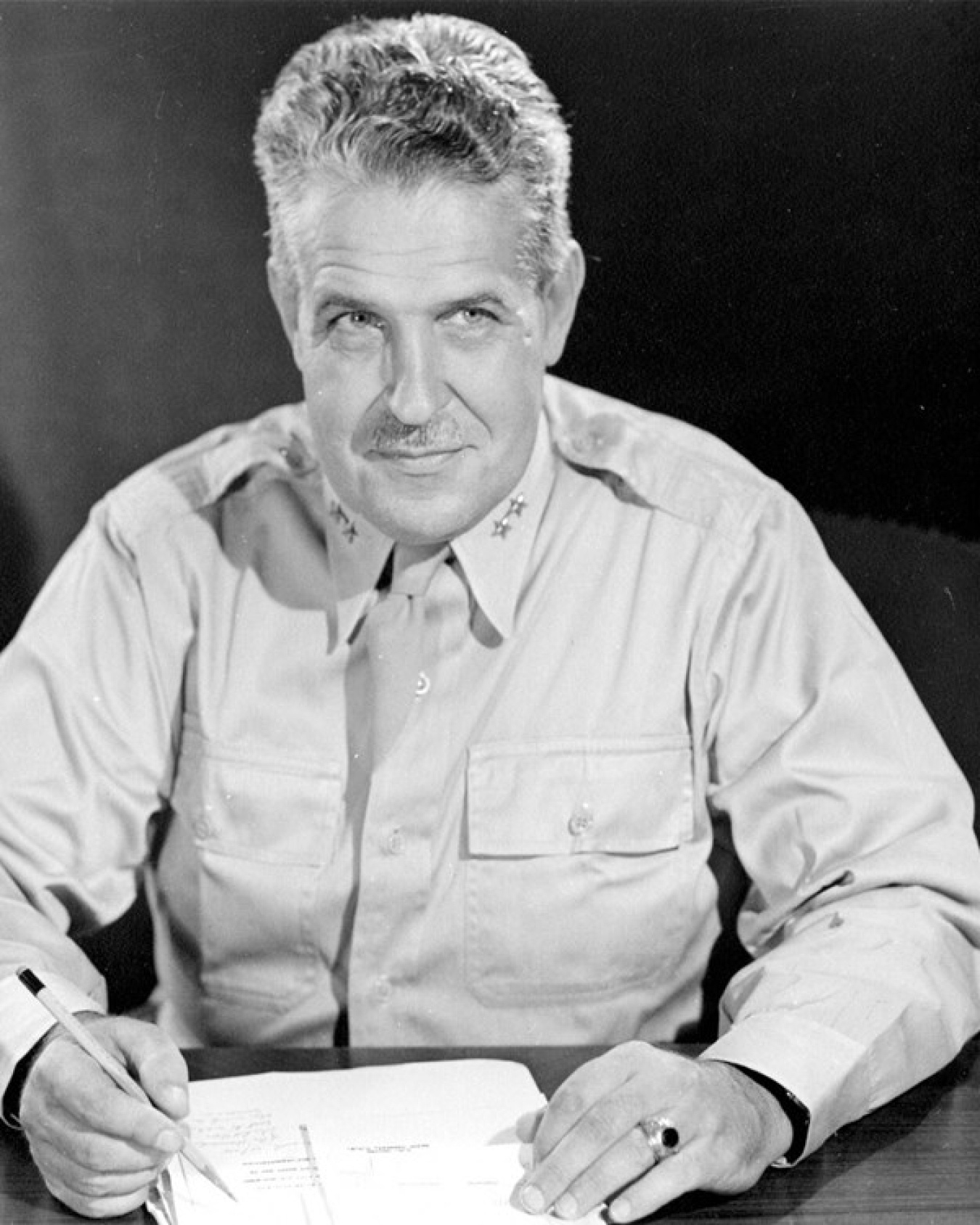

By September 1942, the project’s leaders had come to realize that developing an atomic weapon was going to require an enterprise of far greater scope and complexity than originally anticipated. They agreed to the appointment of an Army officer who would be assigned overall responsibility for all aspects of the wartime atomic program. Consequently, on September 17 Colonel Leslie R. Groves was appointed commander of the Manhattan Engineer District. Groves had recently overseen the rapid construction of the Pentagon and hoped his reward for the stunningly successful project would be duty overseas commanding troops. He recalled that “On the day I learned that I was to direct the project which ultimately produced the atomic bomb I was probably the angriest officer in the United States Army.” But General Brehon Somervell, Commander of the Army Services Forces, told him “If you do the job right it will win the war.”

Groves wasted little time getting to work. On September 18, he acquired 1,250 tons of uranium mined from Africa’s Belgian Congo. To be closer to where decisions on manpower, priorities, and supplies were made, Groves moved the Manhattan Engineer District headquarters from New York to Washington, D.C and kept the moniker “the Manhattan Project.” The next day, Groves approved Oak Ridge, Tennessee, as the location of Site X, a secret uranium-processing facility that would separate U235 from U238 in sufficient quantity to make an atomic bomb.

On the recommendation of physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer – who would go on to become the first director of the Los Alamos Laboratory – Groves selected Los Alamos, New Mexico, as the site of a central facility that would absorb the bomb’s design role and provide largescale dynamic testing, fabrication, field testing, and preparation of the bomb for combat delivery. Additionally, Groves selected the area surrounding Hanford, Washington, to house a pilot plutonium plant.

Starting in 1943, the Army regularly requisitioned military personnel to carry out functions that could not be performed by civilians due to reasons of security or manpower shortages. In January, General Groves requested the Services of Supply to allot military police, medical, and veterinary personnel for a special military police company to protect and service the top-secret operations at Los Alamos. A similar request for additional military personnel to form provisional military police, medical, and engineer detachments at the other major project sites was made in March 1943.

The lack of available skilled workers in the civilian workforce could have doomed the project to failure. There were, however, many soldiers with appropriate experience in Army units stationed across the United States. When a shortage of some 2,500 electricians seriously jeopardized construction schedules at both Hanford and Oak Ridge, Army service commands were directed to furnish whatever assistance possible and supply the electricians needed to meet the aggressive construction deadlines.

Supply problems and personnel shortages complicated Oppenheimer’s task of building a functioning bomb. By 1943, junior scientists were about the only available scientifically-educated manpower, and many of these were subject to the draft. In May 1943 General Somervell created a Special Engineer Detachment, a military organization within the Project allowing qualified enlisted men to work on the Manhattan Project rather than be sent into combat. By 1945, the SED grew to include over 3,000 soldiers scattered across multiple Manhattan Project sites – with 1,800 serving at Los Alamos – working on everything from bomb design to inventory control, often collaborating with their civilian counterparts. Unlike their more celebrated academic counterparts, the SED soldiers were still subject to Army discipline and were forced to undergo drills and physical training in the morning before spending a full day working in the labs. As one veteran recalled, “They wanted us to become a marching group. This was not what we liked to do, and we goofed off a lot.”

Various other types of soldiers contributed to the atomic project. The Military Police were responsible for the complex’s security and the protection of its workforce. Secrecy was so intense, recalled one former MP at Los Alamos: “They never really told us the goal of the Manhattan Project, they just said it would help end the war. But then we did later find out, when they detonated one of the bombs at Trinity.” When rapid expansion of the project created an urgent need for additional personnel to handle classified mail and records, a detachment from the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps was authorized, with an initial deployment of three WAAC officers and 75 enlisted women. From 1943 through 1945, WAAC members also worked in a variety of other jobs, some of which were highly technical and scientific.

Finally, as the creation of an atomic bomb came closer to fruition, the Army Air Forces created the 509th Composite Group to begin test drops. Colonel Paul Tibbets began drilling the 393rd Bombardment Squadron using 5,500-pound orange dummy bombs, nicknamed “pumpkins.”

Starting in 1945 during the Manhattan Project and originally under the responsibilities of the United States Army, the United States conducted aerial measurements to determine the extent of radioactive releases following nuclear weapons testing. After U.S. nuclear testing moved underground, the Nuclear Emergency Support Team (NEST) Aerial Measuring System (AMS) was used to confirm that radioactive materials were not released into the atmosphere.

After the Japanese surrendered in August 1945, concluding World War II, the Manhattan Engineer District continued to manage America’s nuclear program. When President Truman signed the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, and on December 31, 1946, the Army passed on primary responsibility for the future development and control of atomic energy to the Atomic Energy Commission, predecessor to today’s Department of Energy and National Nuclear Security Administration. General Groves summarized the significance of the Army’s accomplishment in his farewell message to the soldiers of the Manhattan Engineering District:

“Five years ago, the idea of Atomic Power was only a dream. You have made that dream a reality. You have seized upon the most nebulous of ideas and translated them into actualities. You have built cities where none were known before. You have constructed industrial plants of a magnitude and to a precision heretofore deemed impossible. You built the weapon which ended the War and thereby saved countless American lives. With regard to peacetime applications, you have raised the curtain on vistas of a new world.”

Today, as America honors the peacetime service and wartime sacrifices of the U.S. Army since its founding in 1775, we also recognize the Army’s role in establishing the National Nuclear Security Administration.