Are Wind Turbines Dangerous To Birds and Bats?

Although wind energy benefits the environment, wind turbines and related infrastructure and operations can affect wildlife, including bats, marine mammals, and birds. The U.S. Department of Energy Wind Energy Technologies Office researches ways to improve coexistence of wind energy with wildlife.

Over the past two decades, improvements in wind turbine design and wind energy project siting have greatly reduced the impact of wind energy development on birds. Today’s land-based wind turbines are larger and spaced farther apart than those in previous years, which means we need fewer of them to produce the same amount of power. Offshore turbines are even bigger. In addition, they are built to prevent birds from perching on them. Thanks to these changes, today’s wind turbines pose little hazard to most birds.

However, as with all man-made structures, wind turbines can have adverse wildlife and environmental impacts. Birds sometimes collide with wind turbine blades, and wind farms have the potential to disrupt bird habitats. However, other man-made infrastructure and forms of human interaction (including house cats) are far more harmful.

To help understand wind energy’s impact on birds, researchers conduct monitoring studies at proposed and operating wind energy facilities. These studies can help inform decisions about a plant’s location, size, and layout to reduce risk to wildlife.

This can include:

- Conducting site surveys to identify the location of raptor nests.

- Conducting visual surveys to document the presence and activity patterns of birds throughout the year.

- Using field monitoring to quantify the timing and magnitude of collisions.

The data gained from these studies can help wind farm developers and operators implement strategies that will help protect birds from wind turbines.

As a source of affordable, homegrown power, wind energy offers many advantages. However, although wind energy sites rank lower than other energy generating facilities in terms of environmental impacts, wind turbines still pose a considerable risk to bats who occupy the same airspace. Some species of bats collide with wind turbine blades. These collisions occur most often during late summer and fall when bats are migrating and mating.

Research indicates that long-distance migratory species, like the hoary bat (pictured), eastern red bat, silver-haired bat, and Brazilian (or Mexican) free-tailed bat, are the most active, and therefore most at risk around wind turbines. Complicating matters, many bat species seem to be attracted to wind turbines.

This is why members of the wind energy industry, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Wind Energy Technologies Office (WETO) and its national labs, and other research institutions support work to better understand bat behavior and lower the risk for all wildlife, including birds, marine mammals, and bats.

Monitoring Activity at Potential Sites

Bats emit high-frequency sounds and listen for the echoes that bounce off the objects around them. This adaptation, which is called echolocation, helps bats navigate their surroundings and hunt for food in the dark.

Acoustic monitoring technology uses special microphones to record bats’ echolocation calls before construction, providing data that can help developers identify which bat species are active in an area. Microphones can be positioned on the ground, but it is useful to mount the microphones higher up—on a meteorological tower, for example—to capture bat activity at the height where a wind turbine’s blades will operate. The Bat Acoustic Monitoring Portal is a useful tool for archiving and visualizing bat acoustic data throughout the year.

In the ocean, floating buoys can employ radar equipment to monitor the behavior and abundance of flying animals, like bats. This would address the challenge of evaluating animal activity at offshore sites that may be in consideration for offshore wind energy development.

As with golden eagles, using radio-frequency tags and transmitters can help researchers learn more about bat behavior, flight patterns, and favored areas or habitats, which can help guide wind energy developers toward sites with less activity and simplify environmental permitting processes.

How Can We Protect Bats and Birds From Wind Turbines?

The easiest way to keep birds safe from wind turbines is to avoid building turbines in areas where birds like to fly, roost, feed, mate, and raise their families. Researchers often conduct field surveys to monitor bird activity and locate nest sites to determine potential risk.

Fortunately, wind energy site developers and operators have several strategies to understand and reduce wind energy’s impact on bats. These strategies (explained further in the sections below) include:

- Screening a potential wind energy site for bat activity.

- Monitoring bat mortality at operating wind energy sites.

- Curtailing wind turbine operation (by slowing, stopping, or changing the direction of blade rotation) at times when bats are likely to be present.

- Discouraging bats from approaching wind turbines with deterrent technologies.

Guidelines and environmental regulations for utility-scale and distributed wind energy projects also help minimize impacts on bats. For example, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Wind Turbine Guidelines Advisory Committee offers Land-Based Wind Energy Guidelines.

Researchers develop ways to monitor and mitigate the impact of wind energy development on bats. These efforts are sponsored by WETO, national labs (see the Tethys database of wind energy and bats publications), and other institutions and collaborations in the industry (like the Bats and Wind Energy Cooperative, an alliance of experts from government agencies, private industry, academic institutions).

Let’s take a closer look at each of these strategies and where they fit into the wind energy site development, construction, operation, and decommissioning process.

Whether considering a site for wind energy development or operating an existing wind energy site, it is important to consider—and strive to minimize—impacts on species like this hoary bat pictured above.Photo from John McGregor, Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources

Whether considering a site for wind energy development or operating an existing wind energy site, it is important to consider—and strive to minimize—impacts on species like this hoary bat pictured above.Photo from John McGregor, Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife ResourcesWhether considering a site for wind energy development or operating an existing wind energy site, it is important to consider—and strive to minimize—impacts on species like this hoary bat pictured here.

As is the case with birds, the best way to keep bats safe from wind turbines is to avoid building turbines in areas with high bat activity. Therefore, when selecting a wind energy site, developers should screen for bat activity during the preconstruction phase—before construction begins. This will help determine the potential impact a wind energy facility will have on local bats.

Screening a potential wind energy site for bat activity involves conducting acoustic monitoring studies to identify species and activity patterns associated with seasonal, weather, and habitat conditions. It is also important to identify any environmental characteristics that may attract bats, including:

- Trees, caves, and similar spaces to roost and raise young

- Migration paths and stopover sites

- Winter hibernation sites like caves, mines, and rock crevices.

In addition to monitoring flight paths of birds, wind energy project developers identify and avoid locations with favorable habitat characteristics. These characteristics include:

- High populations of prey animals

- Areas for nesting sites

- Migration paths and stopover sites

- Winter ranges

- Wetlands and mountains.

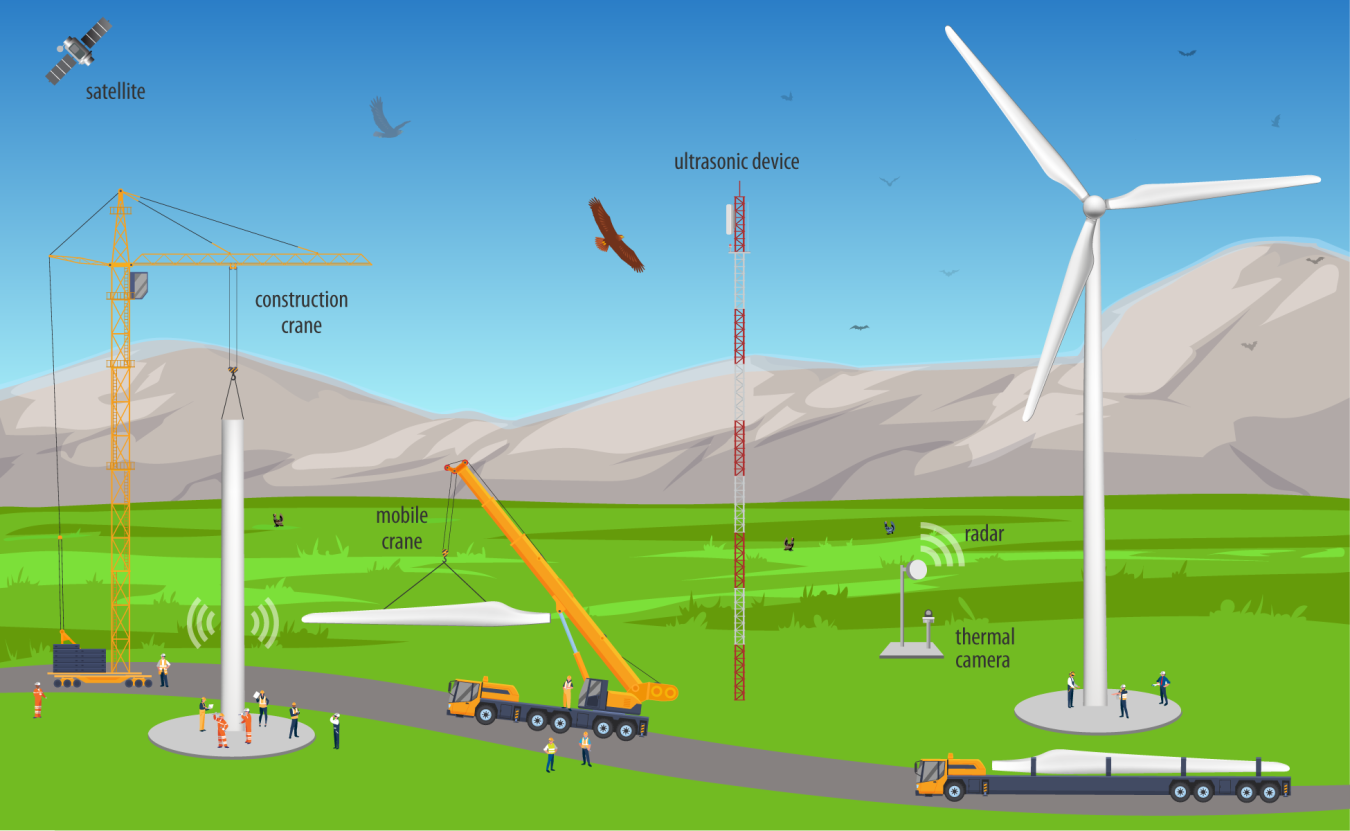

Through the Enabling Coexistence Options for Wind Energy and Wildlife program, researchers at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory collaborate with technology providers to support the development and validation of emerging technologies related to bird and other wildlife interactions at land-based wind farms.

In addition, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory are collaborating on the U.S. Offshore Wind Synthesis of Environmental Effects Research project to assess interactions between offshore wind energy and wildlife, including birds. (Watch a webinar on potential risks to birds from offshore wind energy, behavioral responses like avoidance, and monitoring and minimization technologies.)

Wind energy site developers can use several tools to monitor and predict bird activity. For example:

- The Pacific Northwest National Laboratory’s ThermalTracker 3D system uses thermal cameras to monitor the flight activity of birds and bats at land-based and offshore wind farm sites.

- Radio-frequency tags and transmitters can help researchers learn more about bird behavior, flight patterns, and favored areas or habitats, which can help guide wind energy developers toward sites with less activity and simplify environmental permitting processes.

- Computer models that use the tracking information, like the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s Stochastic Soaring Raptor Simulator, to predict the most likely long-distance flight paths of golden eagles, can also be used to predict bird activity and habitat conditions in specific locations.

- Offshore buoys equipped with Pacific Northwest National Laboratory radar systems to monitor behavior and abundance of birds at potential offshore wind energy sites.

These and other tools can help developers site turbines in lower-risk locations and help operators implement smart or manual curtailment measures to avoid collisions. For example, during annual bird migration periods, land-based or offshore wind power plants can temporarily shut down operations, stopping rotors from spinning.

Researchers and members of the wind energy industry help to mitigate the impacts of wind energy projects on birds using a variety of tools, such as global positioning devices (GPS) or observational records from cameras or ground-based surveys, to track anGraphic by Josh Bauer, NRELAt existing wind energy sites where bats are known to be active, operators can use deterrent technologies to discourage bats from approaching wind turbines.

In some cases, deterrents can help keep bats away from wind turbines, which allows wind farms to operate normally without having to curtail operations when bats are present. However, it is difficult to emit high-frequency sound far enough for bats to hear and be able to respond to quickly enough to avoid the spinning wind turbine blades. Acoustic deterrent devices, which can be installed on wind turbines, broadcast ultrasound, (i.e., sounds above human hearing) at the same frequency bats use for echolocation. This can interfere with bats’ ability to perceive echoes and therefore their ability to navigate and find food. As a result, the bats may decide to move to a different area. Read a short science summary about ultrasonic bat deterrents.

Other studies including national labs and federal agencies have explored whether dim, flickering ultraviolet light can deter bats from approaching wind turbines. Read a short science summary.

Researchers are working to explore new types of and to improve existing deterrent technologies to increase their effectiveness.

Studies explore if ultraviolet lights (like the one pictured) can help deter bats from wind turbines.Photo from Bethany Straw, U.S. Geological SurveyWhen bats are present, or expected to be present, at a wind energy site, operators can curtail wind turbine operations, meaning they slow down or stop the rotation of a wind turbine’s blades. This allows bats to navigate around the turbine’s blades without risk of collision.

Wind farm operators often based their curtailment strategies on the time of year and wind speed. Years of data have shown that bats are most at risk near turbines during late summer and early fall when wind speeds are relatively low. For example, curtailing at night from mid-July to early October when wind speeds are below 5 meters per second has consistently proven to reduce bat collisions. However, curtailment can result in a loss of power generation and may not be an effective strategy for all wind energy sites or for all bat species.

To minimize energy loss while reducing collisions, many wind farm operators use smart curtailment. This approach incorporates additional data like temperature or real-time bat activity measured from acoustic microphones to determine whether a turbine should be curtailed. This helps operators avoid unnecessary curtailment while reducing the wind farm’s impact bats.

When it comes to researching wind energy’s coexistence with birds, endangered and migrating birds are a particular area of concern. The Endangered Species Act protects threatened or endangered wildlife and plants. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act protects migratory birds, making it illegal to, for example, take, sell, or purchase such birds (unless a person has a valid permit).

Wind energy project developers can use Land-Based Wind Energy Guidelines from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Wind Turbine Guidelines Advisory Committee to advance wind energy projects while complying with these acts. The guidelines use a “tiered approach” to assess potential impacts to wildlife and their habitats:

- Tier 1: Preliminary evaluation or screening of sites (landscape-level screening of possible project sites).

- Tier 2: Site characterization (broad characterization of one or more potential project sites).

- Tier 3: Field studies to document site wildlife conditions and habitat, and predict project impacts (site-specific assessments at the proposed project site).

- Tier 4: Post-construction studies (to estimate impacts).

- Tier 5: Other post-construction studies (to evaluate direct and indirect effects of adverse habitat impacts and assess how they may be addressed).

This tiered strategy allows wind energy developers to assess the information they have—and determine what information they need—to make bird-smart decisions about wind energy development projects.

Sign up for updates on the WINDExchange resources.

Relevant Topics

-

- Wind

- Energy Efficiency

- Community Benefit Plans

Learn How Wind Energy Can Create Jobs and Increase Tax Revenue in Your Community -

- Wind

- Energy Analysis

- Deployment

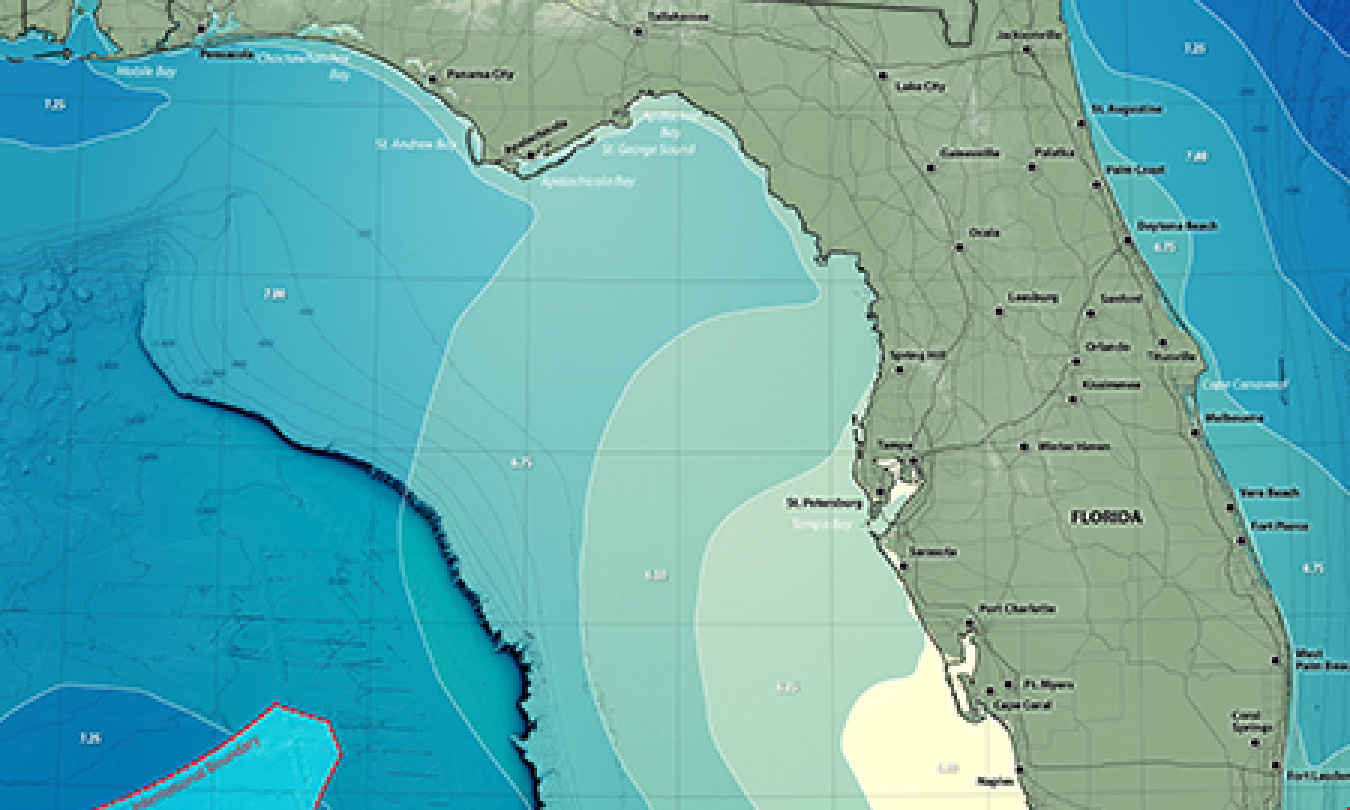

New land-based maps are available for Missouri and Tennessee, and new offshore maps are available for Texas-Louisiana, North Carolina-South Carolina, and Mississippi-Alabama-Georgia-Florida.