A 1963 nuclear test at Shoal was part of the VELA Uniform project.

December 10, 2020

A monument near Surface Ground Zero identifies restrictions associated with the subsurface of the Shoal site.

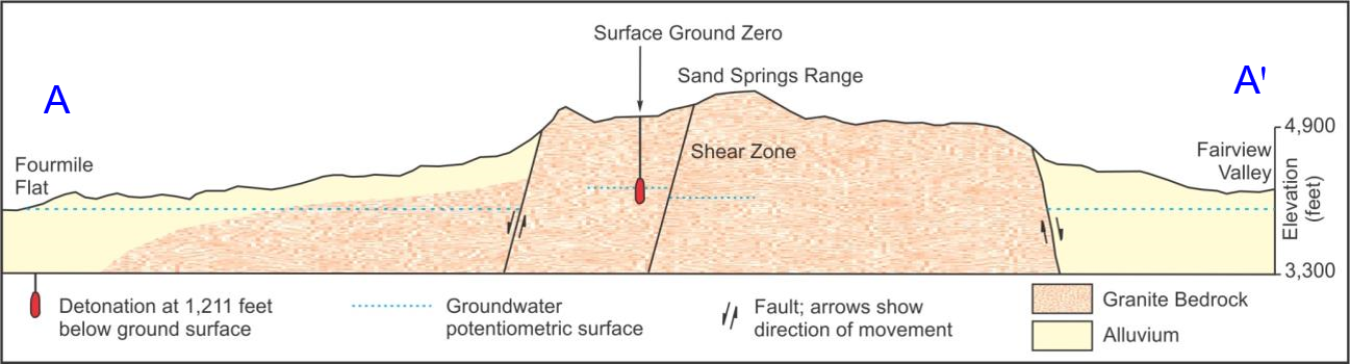

In mid-morning Oct. 26, 1963, dozens of reporters, scientists, and staff from the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission gathered on an overlook to witness the underground test of a nuclear bomb in the Sand Spring Range of north-central Nevada, 30 miles from the town of Fallon. The ground rumbled and dust rose from the desert floor with the detonation of a 12-kiloton nuclear bomb (about 80% of the energy of the bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan) at a depth of 1,211 feet underground.

The Shoal detonation was part of the VELA Uniform project, which aimed to develop methods to monitor compliance with the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty. The Shoal test was designed to determine the effect of a nuclear detonation in a granite rock formation and to compare the seismic activity of natural earthquakes with activity from an underground nuclear explosion. The test would help with detection of seismic signatures indicating banned underground nuclear weapons tests by countries violating the test ban. The Shoal site was selected because it was a seismically active area that would allow comparisons between the test and other natural seismic signals.

No radiation escaped to the surface during the underground test, but subsurface contamination remained at the detonation depth, providing the potential for off-site migration with groundwater. Decades of difficult restoration work, hydrological investigations, and monitoring ensued to check for any potential migration.

A drill rig was used to install monitoring wells in 2014. The wells were completed at depths ranging from 1,570 to 1,750 feet.

To help mitigate potential contamination, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Environmental Management (EM) originally developed a numerical model for groundwater flow at the site to help determine the contaminant boundary around the detonation. The contaminant boundary represents the estimate of how far contaminated groundwater is likely to travel in 1,000 years.

EM installed monitoring wells to confirm the direction and rate of groundwater movement. However, monitoring data from the wells did not support the groundwater flow directions indicated by the numerical model.

The DOE Office of Legacy Management (LM) assumed responsibility for the site from EM in 2006 and started investigating alternative site regulatory strategies. A new approach was implemented by enhancing the monitoring well network, updating the site conceptual model, and revising the site contaminant and compliance boundaries. This work was hampered by the fact that groundwater occurs at a depth of about 1,000 feet and drilling new wells in the granite formation was no small undertaking. Enhancements to the monitoring well network were implemented through a drilling program in 2014 that required a round-the-clock schedule for eight weeks to complete because of drilling depths and difficult drilling conditions.

“We knew we needed to drill additional monitoring wells, but we wanted to make sure we put them in an area that made sense,” LM Site Manager Mark Kautsky said. “We developed alternative site conceptual models that we used to guide where we thought contamination would be detected if groundwater was flowing away from the nuclear test site. We deepened one of the existing wells and drilled two new wells in different locations.”

The new wells were dually completed with a well and piezometer to assess horizontal and vertical gradients.

Monitoring has shown that all contamination has remained within the site contaminant boundary. To accommodate uncertainties associated with the transient nature of the groundwater flow system, the compliance boundary was expanded to encircle the contaminant boundary. These boundaries represent threshold areas that would trigger certain actions if contaminants were detected. Kautsky said that if that were to occur, it could require a revision to the site conceptual model and potential drilling of new wells to further understand the complex groundwater flow system.

After analyzing five years of monitoring results from the well network, the site manager was confident the new site conceptual model allowed LM to move into a long-term stewardship approach. On Oct. 12, 2020, LM issued a closure report for the subsurface corrective actions at the Shoal, Nevada, Site. The report signified that LM was closing the corrective action phase and moving into long-term stewardship of the site.

“In the context of legacy management, this is a significant event,” Kautsky said. “We’re always looking to have all of our sites in long-term stewardship status.”

Kautsky said several LM Strategic Partner (LMSP) team members should be recognized for their work at Shoal, including Rex Hodges, who “understands subsurface conditions at the site better than anybody,” and Rick Findlay, who was “the best manager we could have at the site in terms of unlocking the regulatory framework.”

“We also worked closely and collaboratively with the Nevada Division of Environmental Protection [NDEP] to develop our alternative compliance strategy. Absent the collegial relationship we developed with NDEP, none of this would have been possible,” Kautsky said.

For the time being, the team is confident in the site conceptual model and LM’s ability to monitor the site long-term to assure that contamination does not migrate outside the site contaminant or compliance boundary. Annual site inspections will continue to monitor groundwater elevations and ensure the monitoring wells remain in good condition, but the sampling frequency will be reduced.

“We understand where the contamination is and we’ve been able to show through the passage of time that it hasn’t spread beyond that area. So, rather than sampling every year, we’ve changed the sampling frequency to every three years,” Kautsky said.

A schematic geologic cross section of the Shoal site area.