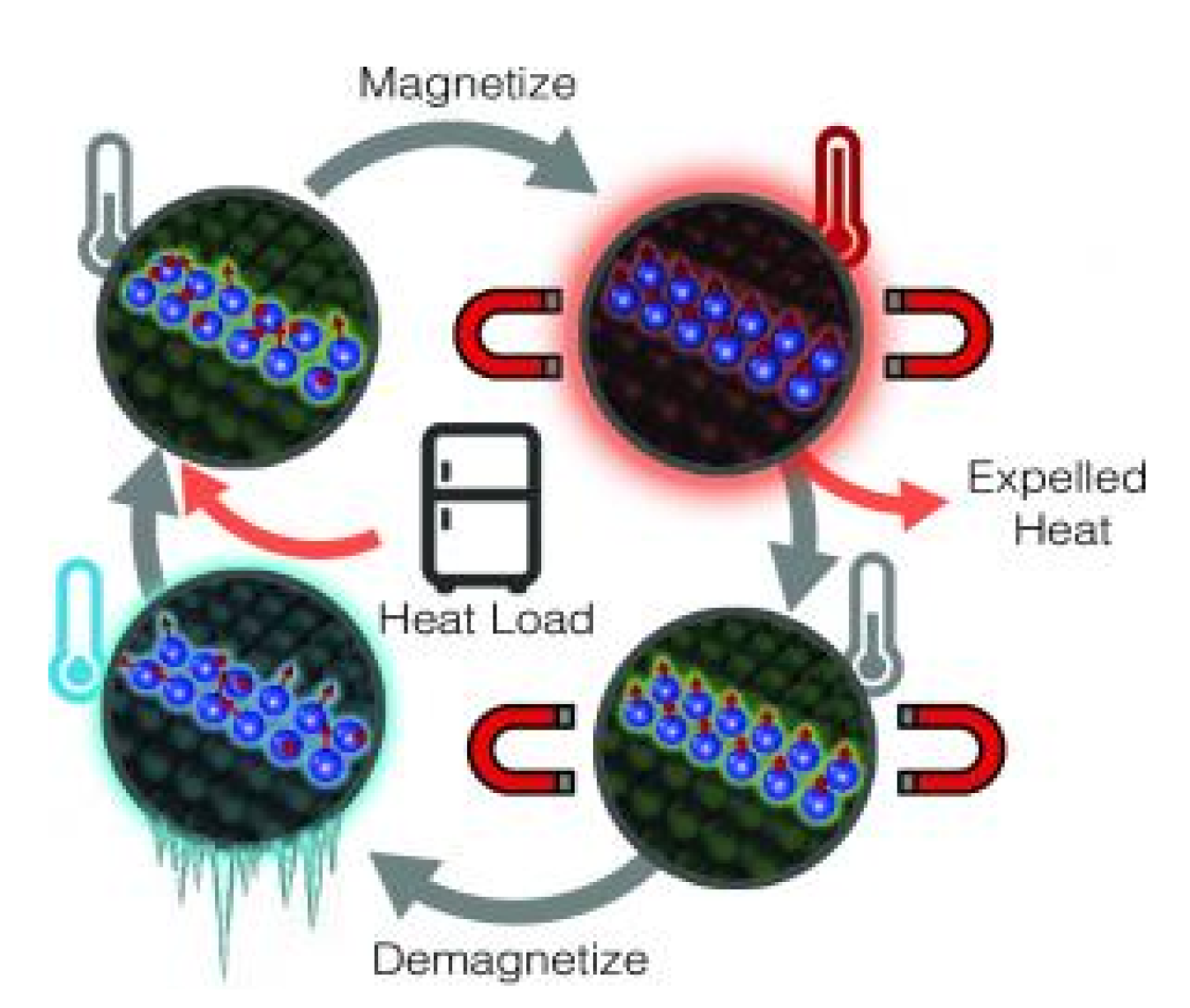

Some metals do a remarkable thing when they’re placed within a magnetic field: They heat up. Remove the magnetic field, and they grow cold.

September 14, 2016

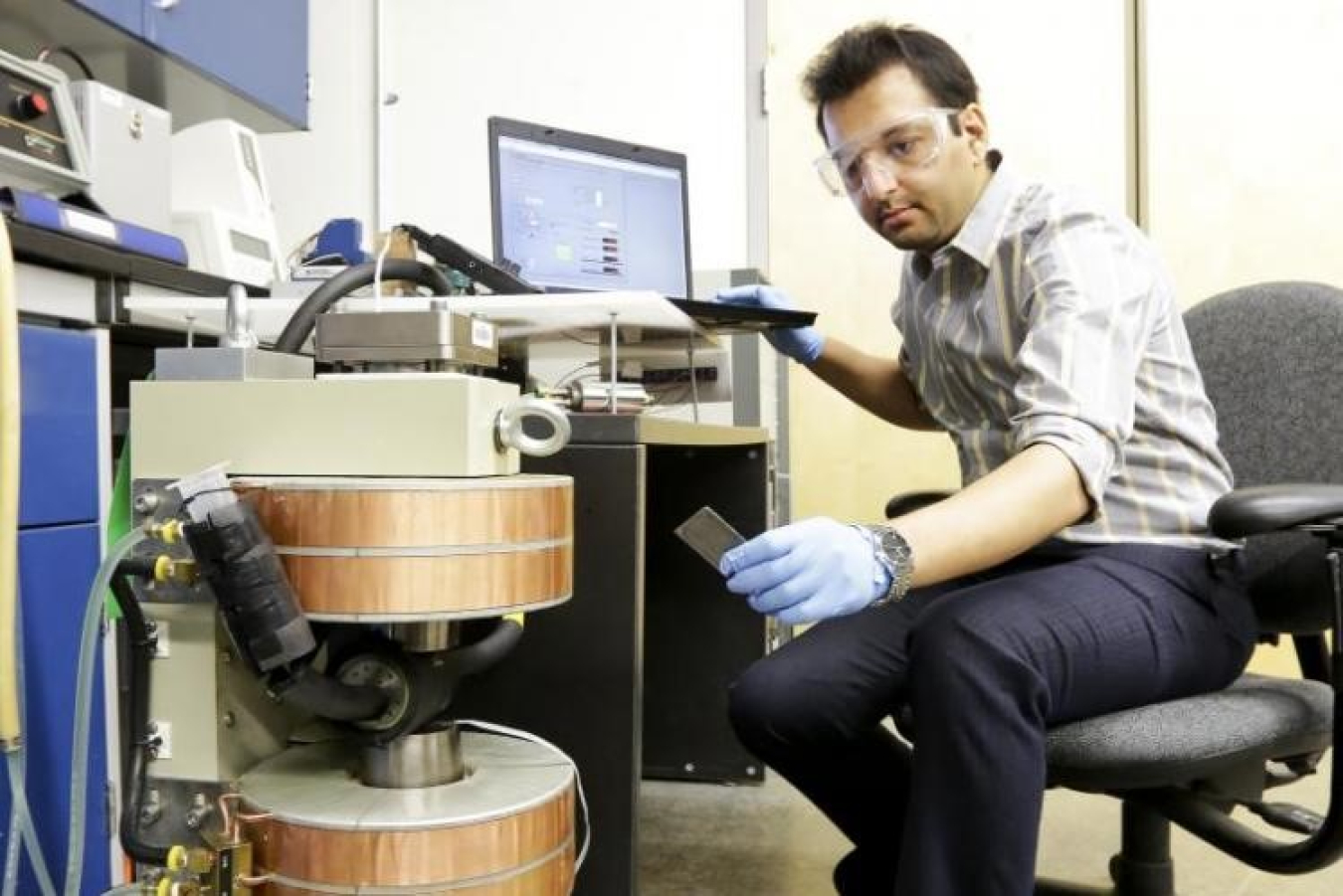

ORNL mechanical engineer Ayyoub Momen works on a magnetocaloric proof-of-concept refrigeration prototype.

This article originally appeared in the Oak Ridge National Laboratory Review Blog on 9/7/16

Some metals do a remarkable thing when they’re placed within a magnetic field: They heat up. Remove the magnetic field, and they grow cold.

It’s not difficult to see how this heating and cooling, known as the magnetocaloric effect, might be put to good use. Refrigerators and air conditioners could not only become more energy efficient but also be freed from century-old technology that relies on environmentally harmful refrigerants.

Researchers with ORNL’s Building Equipment Research Group are working with General Electric Appliances to produce a refrigerator based on the magnetocaloric effect. The ORNL team is also developing an air conditioner based on the same principle.

Their efforts so far suggest such products will be not only greener but also 25 percent more energy efficient than conventional appliances.

“Right now emissions that arise from heating, ventilating, air conditioning, and refrigeration equipment are receiving a lot of scrutiny,” said mechanical engineer Omar Abdelaziz, leader of the ORNL BER Group. “In the U.S., this equipment consumes about 20 percent of the nation’s energy.”

In addition, he noted, common refrigerants are powerful greenhouse gases. The global warming potential for the most common refrigerator refrigerant, for instance, is 1,400 times higher than that of carbon dioxide. The global warming potential of the most common air conditioning refrigerant is 2,000 times higher, and that of the most common commercial refrigerant is 4,000 times higher.

The researchers are experimenting with alloys of lanthanum, iron, silicon, cobalt, and sometimes hydrogen, using the magnetocaloric properties of different recipes to create a practical appliance. Magnetocaloric materials lose their magnetism above a specific temperature, known as their Curie temperature. By fine-tuning the alloy composition, the team can create materials with progressively lower Curie temperatures, allowing them to arrange the alloys to amplify cooling.

Magnetocaloric materials are very touchy, though, so researchers had to overcome some serious practical challenges to take advantage of this oddity of physics.

For instance, a magnetocaloric refrigerator uses a water-based liquid to transfer heat and cool the compartment. If that liquid is simply pushed through the powdered alloy, however, the benefits are offset by the work needed to push the liquid.

One solution is to run the liquid through tiny channels in the material. But to produce those channels, the alloy must be finely ground, which presents the first challenge.

“Any conventional manufacturing processes where we make microchannels requires very fine powder,” ORNL mechanical engineer Ayyoub Momen said. “But as soon as you crush these materials to such a powder, let’s say 5 micrometers, they become so reactive in some cases that they can even become explosive.”

The second challenge, he said, is that the alloys are very brittle, meaning they’re unsuited to conventional manufacturing processes. And, finally, they are heat sensitive.

“In most cases these particles hate heat,” Momen explained. “As soon as you heat them up, they lose their magnetocaloric properties.”

The research team came up with a solution that involves 3-D printing the materials and holding them together with an epoxy. With this process, developed at ORNL’s National Transportation Research Center, they can create channels as small as 100 micrometers.

They also developed the means to heat—or “sinter”—the material to make it stronger without destroying its magnetocaloric properties.

The team is developing a process that uses magnetic fields to cause the powder—and channels within it—to line up automatically, much like the patterns created by iron filings on a piece of paper placed over a magnet.

The researchers have two papers pending that describe their work. Plans call for a magnetocaloric refrigerator to be commercially available by 2020.