LM utilizes lidar technology to ensure that sites are protective of human health and the environment.

July 7, 2020In June 2020, archaeologists uncovered the world’s oldest and largest Mayan monument hidden in the tropical rainforests of Mexico. More than 5,000 miles away, just outside of England’s Stonehenge attraction, scientists found what may be the largest prehistoric structure in Great Britain. Discovery of these ancient wonders was enabled by light detection and ranging (lidar), a laser mapping tool that allowed experts to see through the rainforest’s thick canopy of tall trees and deeper still through layers of earth to trace the structures buried beneath.

When it comes to tracking changes at the United States’ cleaned up nuclear sites, the measurement strategy is not all that different from that of these archaeological quests. In fact, experts at the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Legacy Management (LM) utilize this same lidar technology to ensure sites are protective of human health and the environment, employing it via drones — or unmanned aerial systems (UAS) — for ease of use.

Lidar works by projecting a laser and recording the time it takes to bounce back to the source from the target. The time logged then determines the distance from one point to the other. To measure elevation, lidar can be projected from a raised object with a known position, like a UAS. Before use of UAS, however, LM had to conduct ground-based surveys or hire a pilot and a plane and coordinate with the Federal Aviation Administration to authorize the flight, which was often too expensive.

“It would take thousands of dollars flying lidar by plane to achieve the accuracy that you can get flying lidar via UAS — and even then, you still might not reach that level of precision,” said Josh Linard, a technical data manager for LM who oversees the office’s administration of lidar. “Without an aerial unit, you would have to go out with a handheld GPS and take a measurement, then take a step, then take a measurement, then take a step — essentially surveying every couple of centimeters — to collect elevation data that would match the accuracy of an airborne lidar survey. Fortunately, we can now fly lidar with a UAS in a matter of hours and collect this really high-quality information with far fewer hurdles.”

For most of the LM sites where lidar is used, the objective is to establish a baseline understanding of the area’s elevation as the sites’ man-made monitoring and maintenance solutions settle into their natural environments. LM will then survey these sites every 10 years and compare the new measurements to the original data to identify any shifts and inform long-term land management strategies.

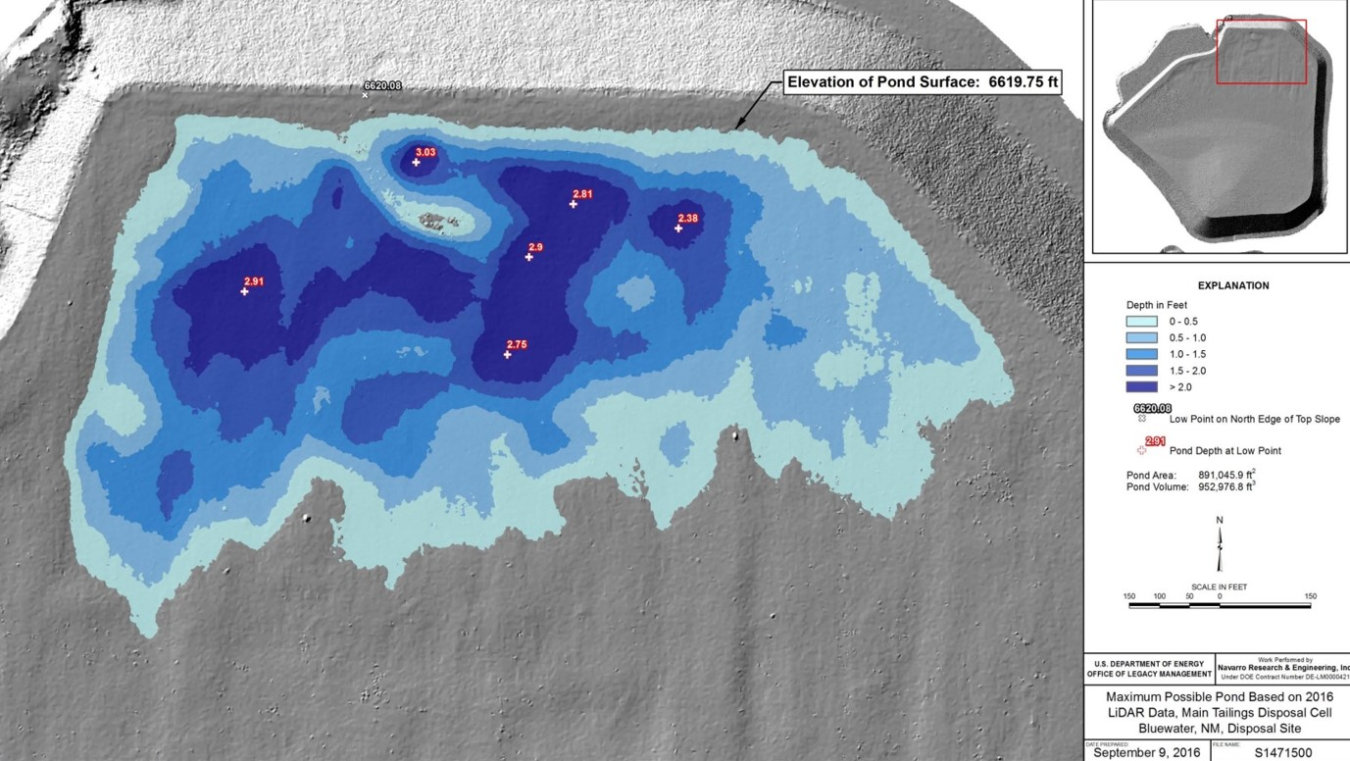

At some sites such as the Bluewater, New Mexico, Disposal Site, a former uranium processing site located about 80 miles west of Albuquerque, LM has increased the frequency of surveys. When the Bluewater site team noticed a depression starting on the surface on the site’s disposal cell — a protective storage unit encapsulating contaminated materials cleaned up from the site — they decided to perform lidar surveys annually to understand the rate at which the change was occurring and determine an appropriate solution.

In addition to improving change detection and data collection, UAS lidar surveys also have the potential to make LM’s site evaluation process faster, cheaper, and — most importantly — safer, reducing the risk LM employees face when traversing rough site surfaces.

“One of the things that we’re really excited about is being able to use UAS to make our work safer,” Linard said. “Right now, we do annual inspections at a lot of the disposal cells — like the one at Bluewater — and these inspections require site teams to walk on uneven ground. While it isn’t common for people to slip, trip, or fall, we still want to make sure all LM workers do their jobs in the safest way possible, and the new lidar UAS flights help with that goal.”

While technology is always evolving, Linard understands that innovation doesn’t always mean a more efficient use of the tax-payer dollars.

“For LM, nothing has been as vetted or as trusted as lidar,” Linard said. “That’s why we continue to rely on it as a key tool in helping inform our plans for protecting human health and the environment.”

This figure shows annual elevation changes determined from lidar data collected at LM’s Bluewater, New Mexico, Disposal Site. Understanding the rate of these changes can inform LM’s long-term surveillance and monitoring decisions.