Tribal Energy: Powering Self-Determination

(NATIVE MUSIC WITH DRUMS AND MEN SINGING PLAYS)

MATT DOZIER: In the United States, there are 573 federally recognized Native American Indian Tribes. Of those, 346 are spread across the contiguous 48 states. Alaska is home to the other 227.

DOZIER: Reservation lands encompass around 57 million acres, with Indian reservations ranging in size from less than an acre to over 17 million acres, the largest being roughly the size of West Virginia.

DOZIER: Some tribes are large, with their own hospitals, schools, and court systems. Others are much smaller, isolated communities, reliant on fragile connections to essential services.

LIZANA PIERCE: Many years ago, David Lester from the Council of Energy Resource Tribes, who has now passed, first told me that if you've met one tribe... you've met one tribe. There is in some places some regional common history, but each tribe is still unique.

DOZIER: That's Lizana Pierce, deployment supervisor for the Office of Indian Energy. Lizana's been with the Department of Energy for more than two decades. And over that time, she’s seen firsthand just how complex tribes and native issues can be.

PIERCE: There are a lot of common barriers, but there are then the very unique aspects as well, depending on the size of the tribe, their history, their culture, their leadership structure, the tax structure. Indian law is about as fluid as you get (LAUGHS), and it changes constantly.

DOZIER: But there's at least one issue that offers a common thread. As you might have guessed, since you're listening to this podcast, that's energy.

DOZIER: I'm Matt Dozier and this is Direct Current, and on this episode we'll be exploring one of the Department of Energy's lesser-known programs, one that is dedicated to empowering Indian Country — both figuratively and literally.

DOZIER: The office Lizana works for — the Office of Indian Energy — is where tribes can go to get help on a wide range of energy-related issues.

(MUSIC ENDS)

PIERCE: I see our role as assisting tribes to fulfill their energy visions. And we do that through financial assistance, technical assistance, education and outreach — we're a small office but over the years I think we've had huge impacts.

DOZIER: She's in charge of soliciting and overseeing the hundreds of tribal energy projects the office has supported across the lower 48 states and Alaska.

PIERCE: The results of the relatively small amounts of money that have been invested have had massive impacts on some of these communities, and now we're starting to have numbers that really are powerful.

DOZIER: Coming up, we’re going to hear from some of those communities — the challenges they face, the energy solutions they’ve pursued with help from the Energy Department... and the impacts those projects have on people’s lives. Stay tuned.

(DIRECT CURRENT THEME PLAYS, THEN MELANCHOLY MUSIC WITH STRINGS PLAYS)

DOZIER: For many, life on an Indian reservation is defined by hardship and struggle.

DOZIER: When treaties and laws like the Indian Removal Act, signed by President Andrew Jackson in 1830, forced Native Americans onto reservations, the lands they were told to resettle on were often small and remote. Uprooted from their traditional ways of life, native communities had to adapt to their new environment without access to the services white settlers enjoyed.

DOZIER: Even today, things like medical care, employment, and reliable electricity are difficult to come by for many tribes — like the Picuris Pueblo of New Mexico.

CRAIG QUANCHELLO: I am Governor Craig Quanchello from Picuris Pueblo. We're located in New Mexico -- in Northern New Mexico. We're located next to Taos, we're about 27 miles south of Taos, pueblo. So a lot of the people in Picuris are on fixed income, or low-income. Our job rate at the pueblo is very low. We're an isolated area, we're about 45 minutes from any kind of grocery store, workplace, jobs. Currently at the pueblo now, if the lights go out or the power goes out, we have no means of calling an ambulance, we have no means of calling fire, so these are some of the things that we're taking in, and we're trying to utilize it around solar. How can we get off the grid for emergencies, stay off the grid for long-term, short-term?

DOZIER: Just keeping the lights on is a significant challenge for some tribal communities — one that’s made increasingly difficult by the threat of natural disasters. In the Pacific Northwest, the Spokane Tribe is wrestling with the effects of climate change on its energy security.

TIMOTHY HORAN: I'm Timothy Horan, I'm the Executive Director of the Spokane Indian Housing Authority with the Spokane Tribe in northeastern Washington. Spokane tribe had fires back-to-back in 2015 and 2016. The 2016 fire was called the Cayuse Mountain Fire, and it destroyed 10,000 acres and took out 14 homes. No one was injured, no lives were lost, which was fortunate. But it did come within a mile of the housing authority office, and the tribal administrative center. The power line, the distribution lines coming into the reservation, were burnt in the fire. So the tribe had no power, and the power was necessary because there wasn't a backup generating system on the pump for the water. It had no independent source of water to fight the fire. I think it was a wake-up call for the tribe. It certainly was for me at the Housing Authority, because it almost took out all of our senior housing as well. That unless we were better prepared, unless we had some independent systems for generating power, that we were going to be at the mercy of the elements. Due to climate change and the fact that our forests are drier, they are more susceptible to fire. We'd had a pattern of fire, more than the Department of Natural Resource on the reservation said that it could remember in, I think, a century.

DOZIER: So each tribe has its own unique priorities, but it can be even more complicated than that. Even within a single tribe, members may be spread out across a wide geographic area, with different issues depending on where they live.

SARAH DRESCHER: My name is Sarah Drescher, I am the Environmental and Energy attorney for the Forest County Potawatomi Community, a tribe with its reservation in northern Wisconsin. And then several other pieces of trust property in both Milwaukee and Campbellsport. The tribe has a number of different challenges. One of the tribe's overall goals is to be 100% energy independent by generating its own electricity, by having its own source of energy through only renewable sources. Energy independence for the tribe is important for a number of reasons. If we're talking about climate change, for example, in times of natural disaster, the traditional grid may not be able to support all sectors of the population. In areas that are more rurally based, that's an even greater challenge because the infrastructure itself is not as developed as in more metropolitan areas. So coming up with a concept that works for both the reservation in northern Wisconsin and then also the properties in Milwaukee where the tribe's economic base is. That can be challenging... So having the ability to have a sovereign energy portfolio, and to be energy independent by producing your own energy, gives you the opportunity to avoid and mitigate some of those natural disasters.

DOZIER: For some tribes that work with the Department of Energy’s Office of Indian Energy, like the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, energy development has a direct link to their economic prosperity.

JOEY OWLE: I'm Joey Owle, I'm from Cherokee, North Carolina and I'm part of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. I'm the Secretary of Agriculture and Natural Resources for the tribe. Energy challenges that we face are around our largest industries. The school, the hospital, the casino, and our tribal services and administrative buildings. This particular project focuses on the secondary casino because it's served by a smaller utility company in Western North Carolina, it's called the Murphy Electric Power Board. Through this project I learned that they are actually about 65-70% of their capacity, the load capacity they can serve for that community. With gaming, it's 24/7/365, we can't miss a second of any kind of power loss for the gaming industry. So what motivates the tribe, in my view, is that with a growing population, the demand for electricity across residential services is going to increase. We're expanding in our economy with our primary Harris Cherokee Casino in Cherokee. We've broken ground on a new 400 or 500 room hotel, 100,000 square foot convention center. They're also looking at expanding into an outdoor shopping area. So the casino represents the largest service load for the tribe. As we're moving forward, again, we need to look at how can we reduce our carbon footprint, and also looking to supply our own demand.

DOZIER: So far, we’ve heard from tribes in the contiguous United States, but there are hundreds more Native communities in Alaska. Many of these are located far from any kind of infrastructure, and more often than not depend on fuel flown in or barged into the community for survival.

HUGHES: My name is Frannie Hughes, I am from Fort Yukon, a village of Athabascan descent, and we like to refer to ourself as Gwich'in people from Gwitchyaa Zhee. And Fort Yukon in our Gwich'in language means "People of the Flats." We're a very remote village. On the map of Alaska, we're up in the northern-eastern part of the state along the Yukon River. We're actually a hub village, but we don't have any roads that you can drive out of Fort Yukon to. We can travel on that river by boat in the summertime and bring supplies in. Other than that, we're isolated -- to bring anything fresh in we have to fly it in. It's very expensive. Easiest way to set up electricity in a remote site, like where we are, is to bring in a diesel-operated generator. They're easy to transport, they're kinda tough. They drink a lot of fuel to operate, and that brings the problem that the pricing is high, and not only does the price get to be expensive, but we couldn't depend for it to be on all the time, and we didn't really have good reliable electric resources. We have to keep our water moving, because we have extreme weather to where it can get 50 below for a month. It could then warm up to maybe 20 below. It's still so cold that that water cannot stand still, it has to always be circulating. It takes the hookup to the power plant to keep that going. When our power plant was going down I thought, "What can we do here?"

(OPTIMISTIC MUSIC WITH CHIMES AND STRINGS PLAYS)

DOZIER: What they did — and what everyone we spoke to for this episode has done — is reach out to the Office of Indian Energy. Lizana and her colleagues work with tribes and native communities to identify their biggest energy needs, and the best ways to address them — whether that’s through technical expertise, education & outreach, or financial support.

PIERCE: Financing and funding is the number one barrier, without question, that's come up over and over and over again. So since 2010, the Office of Indian Energy has provided $85 million to over 180 tribal energy projects, valued at about $180 million. So even though our average is about $8.5 million a year, there's been some massive, tangible results. Last year alone, with the projects we funded, it's estimated to result in another 19 megawatts of systems, which correlates to somewhere in the neighborhood of $260 million over the course of those projects because they go 20-30-plus years depending on the technology type. So we're talking real money. And then, leveraged with cost share and then the life of the systems, it's kind of like the gift that keeps on giving, year after year. So that's been really, really exciting. Because we are now, instead of studies and paper, have helped the tribes install hardware in the ground and save money that could be used for other priorities within the community, which are many, usually.

DOZIER: The cost share she mentioned is how the office funds projects — splitting the cost with the tribe 50-50, as required by law.

(MUSIC ENDS)

KEVIN FROST: The unique thing about this office is it actually is a partnership.

DOZIER: That’s Kevin R. Frost, director of the Office of Indian Energy.

FROST: So when it comes to working together, it’s not either this office or the tribe taking the lead, it’s both of us working in concert in order to tackle a specific issue. And the reason that's so important with this office is, what we like to say is it’s a "do-with" office, not a "do for," and what that means is we partner with you, we work with you, you establish ... what type of technical assistance you might require, or even when it comes to project development, what type of project development you want.

DOZIER: He said the office is “technology- and fuel-neutral.” So the projects it supports reflect the individual needs of the tribes, and the resources they have available.

FROST: 15:16 Now, the one thing that when we look at these specific obstacles, is we don't tailor anything for a one-size-fits-all approach. That's never worked, and it will not work. What we do is by partnering and working on an individual basis, that allows us to address some of those direct obstacles. But it also gives tribes the opportunity to come up with their own solutions as well to drive that conversation.

DOZIER: More often than not, these days, that means solar — especially in places like Northern New Mexico for the Picuris Pueblo and Governor Craig Quanchello.

QUANCHELLO: Our project with DOE at Picuris Pueblo has been about solar. Picuris has good wind and good sun, and our altitude, it's cool. So we're an ideal location for solar. We've been trying to develop community solar to offset the community's electric bill, being that in our area of Northern New Mexico the electricity is really high in our area. So we've been fortunate to get one project, a 1-megawatt array, and just been awarded another 1-megawatt array for the pueblo -- a million dollar match with the Department of Energy. And the thing that we liked about solar is that it would benefit the community itself. It's something they can see, something that will affect their daily lives and help their daily lives. So once that was in place it just took off from there. The challenges of the community at Picuris Pueblo has been just not understanding what solar is and how it works. We didn't know what a megawatt was. Yeah. At the time there's not a lot of places that were doing a megawatt. Everybody was residential, they're doing little solar farms and whatnot. But 1 megawatt is about 4,000 panels. So once we realized that, the scale of the solar, it was eye-opening and it was exciting.

DOZIER: The Southwest isn’t the only place solar makes economic sense. Lizana said its low cost, reliability and longevity has made it a go-to option for native communities across the lower 48 and Alaska. Timothy Horan outlined the Spokane Tribe’s solar installation in northeastern Washington.

HORAN: We are doing a solar project, the Children of the Sun Solar Initiative. The tribe historically has called itself the Children of the Sun. Our project is 650KW of solar panels that'll be on 28 tribal buildings at Wellpinit, and Wellpinit is the administrative center of the Spokane Reservation, and it is estimated that it will reduce the power load of the reservation (or at least in Wellpinit) by about 28% and save us $2,900,000 over the life of the project. The project will make a huge difference for the tribe. We'll be training 6 to 8 tribal members. We expect employment that could be generated, through that activity and other follow-on activity, it could support maybe 4-6 jobs. So we've got that level of skill development. We're also working with the school system so we can begin to integrate an understanding of solar and renewable into the school system and raising the generations that are coming up to be aware and interested and involved. It will cut the energy cost to the tribe and it will give the tribe more disposable revenue they could use in other ways. Tribes are usually pretty strapped for revenue, often grant-dependent. So if you find a way that you can save money and deploy it differently, then that's a huge plus.

DOZIER: Most of the projects supported by the Office of Indian Energy today are modest, community-scale endeavors — smaller than a big grid-scale power plant or solar farm, but Lizana said that’s way bigger than tribes were installing 20 years ago. Plus, the impact of those cost savings, and the symbolic value of a tribe controlling its own energy source, can be even more important than the numbers reflect.

DRESCHER: The Forest County Potawatomi Community has been very lucky to receive several grants through DOE. The projects that have been developed to date are allowing the tribe to save considerable dollars on their energy. The initial solar project that the Forest County Potawatomi Community installed was in 2013 and 2014. That was a phased project that I believe there were 15 buildings overall that solar was installed on. If you're saving nearly a megawatt on energy costs in the course of a year, the immediate financial gains are significant. In addition, the panels are very visible. They're located in areas where not only community members but Wisconsin citizenry as a whole can see these and can recognize exactly what it is that the tribe is trying to do. The tribe stands behind its commitment to the environment, and this is a piece that physically shows that commitment. It's a very powerful message.

DOZIER: For some, an energy project supported by the Energy Department is just a stepping stone to even more ambitious goals.

OWLE: In 2016 we received a $1 million grant from the Department of Energy to deploy a solar PV project on a community scale. The target was called our secondary casino, which is called the River Valley Casino and Hotel – Harrah's River Valley and Casino hotel. The project served four buildings: a 300-room hotel, a little over 100,000-foot gaming floor, and two administrative buildings. What was originally planned for a 1MW solar farm was redesigned for 700 watts based on the budget and area we had to work with. So for this project and our future, we're reducing the amount of energy consumption for an essential function of the tribe, which will reduce our carbon footprint, commence us to that rhetoric that we're serious about our future with our energy needs. And this is a great springboard into larger projects.

DOZIER: Now, as I mentioned earlier, solar isn’t the only type of energy generation being deployed on native lands. In Fort Yukon, a new biomass plant built with support through the Office of Indian Energy and many other partners is now providing power and heat to the Gwichin community, fueled by wood instead of expensive diesel.

HUGHES: In February of 2017 we went online with the new generator. It was as if you could just hear that domino effect of the echo of people cheering all over, because this brought employment to our community, it brought us together in a lot of ways. Now we're capturing our waste heat that used to go up into the smokestacks, and we've installed a heat loop in our community, that we're providing the waste heat with backup biomass heat up to our school, to our school buildings, the admin building and the garage that the school bus is in. And the gymnasium that our whole community uses as a community building. And it goes all the way up and it keeps that water treatment center that is so expensive to use, it keeps it heated.

(ATMOSPHERIC MUSIC WITH SYNTH AND STRINGS PLAYS)

DOZIER: As important as reliable electricity is to our daily lives, these projects can have a profound effect on a community’s resilience — even its survival. As Lizana explains….

PIERCE: You look at in California, where utilities are shutting off major transmission lines, people are going weeks without electricity. Some of the tribes in California already have microgrids. They can just disconnect and continue on. So some of these other things now, are driving decisions on being self-sufficient in your energy. Seniors need medical attention, you've got medicine that needs to keep frozen, you have businesses that need to keep operating. This is sustainability, this is survivability in some cases. There is a beauty to energy sovereignty, if you will, developing it locally and having that stability.

DOZIER: Sovereignty. That’s a word that came up over and over in these interviews. It gets to the heart of what native communities everywhere are striving toward, things like self-sufficiency and self-determination.

FROST: When it comes to energy development, if we look at it through that lens of our tribe’s ability to take care of itself and its people, then obviously we need to start with power generation.

(MUSIC ENDS)

DOZIER: Office Director Kevin R. Frost.

FROST: Power is the nexus for everything, not just within Indian country or Alaska communities, but in society at large. You can't have economic development, you can't have financial growth, you can't offer economic growth, jobs, all those other things without a power source. So, understanding that - that's the first area that we hit.

DOZIER: For tribal leaders like Craig Quanchello, reducing energy costs and improving reliability is a big step in that direction.

QUANCHELLO: The benefits of solar at Picuris with this 1-megawatt array has offset their bills, their electric bills, their monthly electric bills, by $75. We plan to eventually offset 100% of their bills. As far as changing the future of the pueblo, I think it already has, in a positive direction. To find more ways to utilize renewable energy. Right now one of our primary goals in renewable energy is to be off the grid for emergency support. As far as me, myself? Being the governor of the pueblo, I'm very proud of it. I think it opened up a lot of doors, it educated a lot people. It's simple. And it makes me proud knowing that we're doing our part. So I'm very thankful for the Department of Energy.

DOZIER: Resilience is another consistent theme when it comes to tribal energy development, especially in areas that have seen heavy impacts from natural disasters. Here’s Timothy Horan again.

HORAN: Resilience is huge. Yeah. I don’t know how it could not be unless you’re just not paying attention. Energy is important for the tribe for several reasons, but energy sovereignty and self-sufficiency, resiliency, as I said, our ability to operate in an emergency for the tribe. Not to be dependent on external forces or powers or businesses, to be able to conduct its business. I think it was kind of an a-ha moment for the tribe, it's like... because systems usually operate, you don't have to think about them, but when they don't operate and you do have to think about them, you're going, “Wow, we're pretty vulnerable here.” So what can we do about this? For a tribe, sovereignty, achieving sovereignty, whether it's fiscal or on a government-to-government basis, or on an energy basis, these things are incredibly important because those are the things that help to determine whether you control your own destiny or not.

DOZIER: Sarah Drescher echoed that sentiment.

DRESCHER: Sovereignty in Indian country is a powerful tool for tribal nations. For Alaskan Native villages, for pueblos, for any iteration of Native peoples. The ability to control one's destiny, the ability to control one's reservation property without hindering development, economic opportunity, while providing adequate healthcare, and providing housing and necessary living opportunities for tribal members runs through every thread of what a tribe does. Native responsibility stems significantly from the environment. So climate adaptation, climate change, those things play a much more impactful role in the native world than they do maybe in everyday society. So sovereignty is one tool through which tribes can really take control of their destinies and empower their people, and make sure their reservations and their homes are protected and secured for the long term.

DOZIER: And that’s one of the primary goals of the Office of Indian Energy: providing the tools, expertise, and funding tribes need to shape their future.

DRESCHER: The opportunity to receive grants for Forest County Potawatomi Community, but also for all tribal communities, is one of the most profound things that the Department of Energy provides. The commitments of tribes to the environment, the ideas of tribes, they're very progressive and they are holistic. The concepts that tribes try to forward, they're not simply "Let's install solar panels so that we have an opportunity to save money," but it's "Let's install solar panels so that we're lessening our carbon footprint and we are taking care of a world that needs pretty consistent care at this point." And although tribes have those ideals and those ideas, the funding is not always easy to find.

DOZIER: To Joey Owle, the progress his tribe has made has come through continuous struggle, with aims to push even further forward in the years to come.

OWLE: We're seeing this investment from those previous generations come to pay off. Where we're at, with the benefits, the services that we have — our previous leaders, community leaders really literally had to go fight for the funding to bring us to where we are. I think what you always hear from tribes, when we talk out what is our reasoning behind this, and for what I've been brought up hearing, is sovereignty. How can we call ourselves sovereign if we're dependent on multiple functions? Energy independence is a component of our sovereignty. Now, will we supply 100% of our electricity needs? It's to be seen. That's the hope, is yeah, I want to see this big grandiose project planned, constructed, implemented, and to see that we are taking our own independence and sovereignty in our own hands by investing in this industry and to meet the needs of our community members.

(POIGNANT, RISING MUSIC WITH PIANO & ORCHESTRA PLAYS)

DOZIER: Frannie Hughes said the impacts in her community have been dramatic, from keeping critical services running to recapturing the less tangible, day-to-day aspects of life in a Native village.

HUGHES: Waste heat with new technology has provided that for our community, and the savings --- that we don't have to bring in 100,000 gallons of diesel that we have to pay to accompany that is not Gwichyaa Gwich'in-based. That money stays in our village. We don't have to breathe that in emissions. We're healthier. Our children are warm in the school. It just is a good feeling, that this will be one year here that they will have monies that we could put towards programs for advanced education projects. And keeping our culture alive with our children, our future. And that is the best benefit that a person could ever come up with. I look forward to the day in the future that we can bring in to our power plant solar panels with backup battery. Even though we are 8 miles above the Arctic circle, we do get a lot of summer sun, and I just think it would be glorious for us to hear old Esa sweeping the front of his porch from the dust instead of hearing the hum of a generator going. Because when we turn that gen off and the solar panel’s providing the power, the energy that we need, that would just be taking us back to where we came from. The reason that we settled in Fort Yukon, in Gwichyaa Zhee.

(MUSIC SWELLS, THEN ENDS)

DOZIER: All of these interviews were collected at the Office of Indian Energy’s annual Program Review, where tribes from every corner of the contiguous 48 states and Alaska gather to discuss their energy development, celebrate successes, and share lessons learned.

PIERCE: Over the last 20 years, I've seen phenomenal changes within the tribes and within the program review. It's magic, when you get people together. The sophistication of the presentations is just phenomenal, videos and drone flyover footage and things like that. And getting that national perspective is huge. And as far as I know, it's one of the very few forums where this occurs. You can see case studies or individual presentations in different conferences and such, but to get 40 or 50 tribes to tell their stories about their energy development and their projects in one room, from coast to coast and up through Alaska — it's pretty powerful.

DOZIER: There’s another dimension to that meeting, as well.

FROST: It also gives tribes the opportunity to network with each other, to talk to each tribe, tribe to tribe on a nation-to-nation basis, and begin to see where their synergies lie, what are some of the best practices. We hear this phrase a lot, but it's absolutely true, there's no reason to reinvent the wheel. If one tribe struggled through it, they may have the capability now and capacity to go ahead and help another tribe by not making those same missteps, and begin to have a more focused approach.

DOZIER: For Kevin R. Frost, there’s also a personal side to the work his office does.

FROST: My mother is Navajo, traditional speaker, fluent. On my father's side, he's Southern Ute, and I'm actually an enrolled member of the Southern Ute Tribe. I actually grew up on both reservations, Navajo and Southern Ute. And along various times of being raised on and off the reservation, I did not have running water. I did not have electricity. So I understand what it means to maximize an important vital resource. And when you're hauling water, whether it's for yourself, your family to use or whether it's for your animals because you utilize animal husbandry, subsistence living — things I've also done in my past as well — it makes you not only appreciate the modern conveniences we have, because people don't understand in today's fast paced world, how much of a privilege — and I'll say that it's an actual privilege — to be able to turn on the switch to get some light, to be able to turn on the thermostat to get some heat and to go right down to a grocery store if you have the funds available to be able to purchase food.

DOZIER: He said that experience gives him a deeper understanding of the ways those hardships affect people’s lives.

FROST: Having been there having been with my people, my people know me, I'm connected to my community. Those things mean a big deal. When you go out and you speak with other tribal leaders, you go out and speak to tribal communities. And earlier when I did reference not having running water and electricity and also gives me not just empathy as well, but it also legitimizes someone in my role when I interact with these communities because I know what that struggle is, and I know what it means to have that type of transformational generational change because it is real and it is there.

DOZIER: And building that trust is a crucial element of working with tribes.

FROST: The one thing that we try to not do in this office is make promises we can't honor, and try not to get ahead of ourselves in terms of having an ego within this office. When you do have that air of humbleness around you as an office, tribes come through our front door, and the one thing that we always try to stress here is we're equals, we're partners. And we respect that. And we understand that as tribes are going through the motions to accomplish a lot of their energy development goals. There is that respect there. And in some cases of our office, there is the admiration because we do see some of those tribes pushing forward, moving the needle, wanting to have greater conversations, and some cases that goes far beyond our own office.

DOZIER: Going forward, Director Frost said he sees big potential for tribes to take control of their energy futures and even go further than meeting their basic needs.

FROST: At least right now, what we're really starting to see in terms of trends, power generation, commercial scale, there are a lot of tribes that don't even come through our office, but they're going to be major players and solar, geothermal, biomass, hydro, in decades to come. There are a lot of tribes that are positioning themselves right now to meet that need of not only supplying power to their own tribal communities, but selling that excess power to off-takers and then using that revenue to either stand up programmatic features on the governmental level, or possibly new endeavors.

DOZIER: For that to happen, though, they’re going to need investment beyond what the small-but-mighty Office of Indian Energy can provide. One potential avenue for that sort of financial backing is the Department of Energy's Tribal Energy Loan Guarantee Program. Doug Schultz, Director of Loan Origination for the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office, explained how his office could step in and help get a tribal energy project off the ground.

DOUG SCHULTZ: So the tribal energy loan guarantee program is relatively new. It's the newest one in our portfolio. And what it does is it focuses on tribes specifically, so the tribes themselves or tribally owned companies that are looking to do energy development. And it's across the spectrum, almost anything you can think of that's related to energy. It might be energy efficiency, it could be generation, it could be transmission. So it's trying to help bridge a gap where tribes may not have a lot of experience with private lenders or private lenders may not have a lot of experience with them.

DOZIER: The program’s substantial loan guarantee authority means it has the ability to support projects far larger than a community-scale solar farm. We’re talking grid-scale potential here — but with bigger projects comes a lot more up-front work — and lengthy timelines to match.

SCHULTZ: Right, they can definitely be much bigger, we have $2 billion dollars of authority for the entire program. So that means that we can do up to $2 billion worth of loans.

DOZIER: The program’s whole ethos is about supporting energy innovation and development projects in places — like Indian Country — where private sector investors might otherwise shy away from the risk.

SCHULTZ: I mean, that's what we do here right? So, you know, we are used to kind of tackling these challenges, understanding what the issues are, mitigating risks, understanding what those risks are, so that that we can articulate that to our, our stakeholders in the building, but also, you know, outside and so, by doing that we help you know, clear the path for other lenders to come in as well. It's as easy as just picking up the phone and giving us a call. Just start the conversation is the most important thing, and it’s easy.

(NATIVE MUSIC WITH DRUMS AND GIRL SINGING PLAYS)

DOZIER: Massive projects like Director Frost envisions may still be years away at this point, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t making progress. And evidence of the program’s effectiveness is everywhere, from the annual program review to the communities where reliable electricity and lower energy bills are changing lives.

FROST: So when we see great things like that happening, it always reminds us here within the Office of IE that 1) we're completing our mission, but 2) with the tribes leading the charge, eventually, sometime in the future it would be great to actually pull this office down because we've actually met our mission.

DOZIER: For now, though, there’s still a lot for the office to do. And after two decades of doing this work, Lizana said she’s still passionate about the mission.

PIERCE: I mean you can't help but be moved when you get a call from somebody that basically says help me, I'm trying, I can only work part-time because we're freezing. We're sitting here with our coats and our gloves on, we can't really type, we can't type with our gloves on, please help us! I mean that's the kind of stuff, the reason we're here every day. But some of these situations are pretty dire. And you cannot help but feel satisfied that you're touching people and making a difference.

(MUSIC FADES OUT, SOFT AMBIENT ELECTRONIC MUSIC FADES IN)

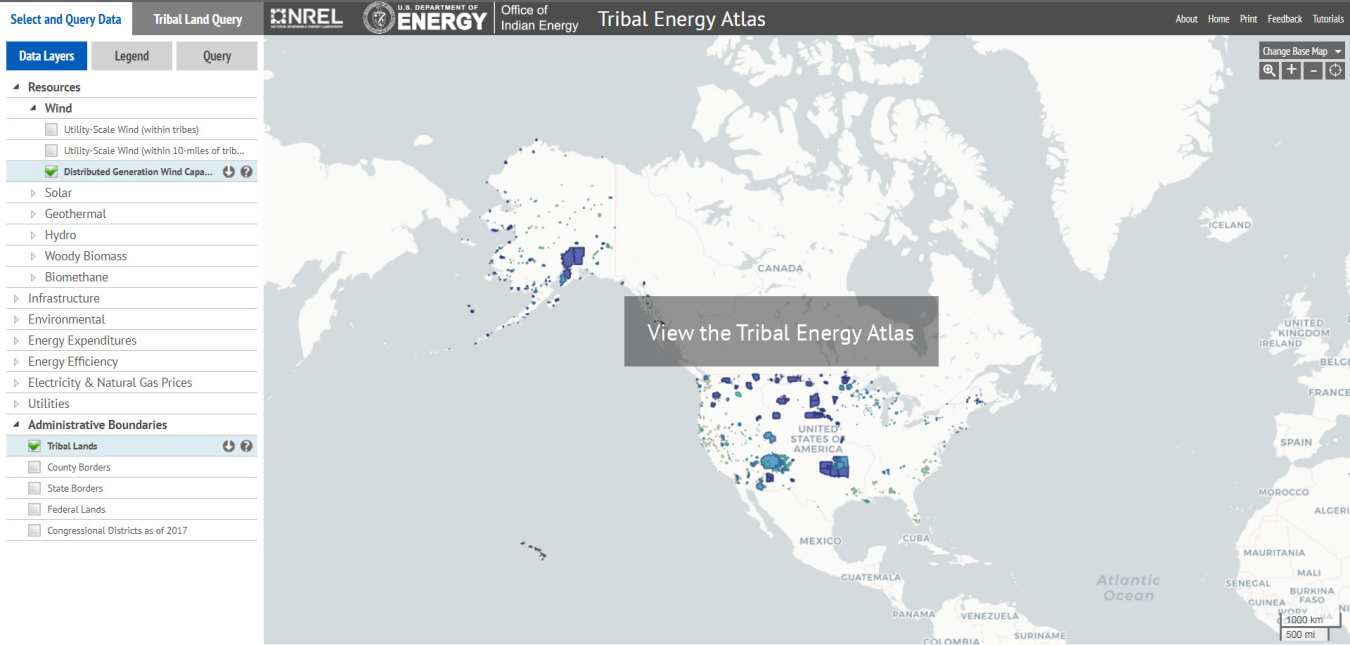

DOZIER: That's it for this episode of Direct Current. If you want to learn more about the life-changing work our Office of Indian Energy supports, visit our website, energy.gov/podcast. We’ll have photos, videos, and links to resources like the Tribal Energy Atlas, an interactive map of energy projects on reservation lands.

DOZIER: Thank you to Kevin R. Frost, Lizana Pierce, and the rest of the Office of Indian Energy staff for their help with this episode, including recording the interviews with Governor Craig Quanchello, Timothy Horan, Sarah Drescher, Joey Owle, and Frannie Hughes. A big thank you to all of them for lending their voices.

DOZIER: Thanks as well to Doug Schultz from our Loan Programs Office. Cort Kreer helped with transcription for this episode.

DOZIER: As always, if you've got a question or want to leave us some feedback, email us at directcurrent@hq.doe.gov, or tweet @energy. If you want to help us reach more people, consider recommending Direct Current to a friend or rating us on Apple Podcasts.

DOZIER: Direct Current is produced by me, Matt Dozier. Sarah Harman creates original artwork for each episode.

DOZIER: We’re a production of the U.S. Department of Energy and published from our nation's capital in Washington, D.C.

DOZIER: Thanks for listening!

(MUSIC FADES OUT)

For hundreds of Indian tribes and native communities across the United States, energy represents many things...

...a lifeline, a source of income, a path to sovereignty. No two tribes are alike, which is why the Department of Energy's Office of Indian Energy partners with tribal communities to develop energy projects that fit their specific needs. On this episode, learn how this small office delivers a big boost to tribes' efforts to take control of their energy destinies.

Tribal Energy Atlas

Developed by researchers from DOE’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory for the Office of Indian Energy, the Tribal Energy Atlas is the most robust tool ever designed to assist tribal energy project planners, technicians, and investors with analyzing energy options in Indian Country. See for yourself!

VIDEO: Southwest Tribes Go Solar

See how tribes in the Southwest are tapping abundant solar resources to benefit their communities. This video celebrates successful U.S. Department of Energy investments in the energy futures of two Arizona tribes: Tonto Apache and San Carlos Apache.

There's a Map for That

The Office of Indian Energy supports hundreds of energy projects on tribal lands — and now you can explore them all in one place! From solar farms to energy efficiency projects, browse our Tribal Energy Database to learn how these efforts are helping tribes and Alaska Native villages move toward energy sovereignty, one project at a time.